Prologue ONE:

My sister Patty passed along the letter to me, from an old friend of our mother’s and father’s, who wanted to know if our parents were still alive. It had been seventy years since he’d last seen them, but he was hopeful. Neither I nor my sisters could ever remember hearing our parents say the man’s name: Victor Sabattini.

The letter was brief: he lived in Florida, and way back then they had all been on a magazine-selling crew together, more than a year. But after they all left the crew, he’d never seen them again, and they’d only at first exchanged a few letters and photos; yet he had warm, rich memories. Recently he had felt strongly compelled to reach out and see if he could find them. His determined search had at last located my sister in Boise, Idaho.

Victor Sabattini, as I calculated from his surprising letter, must be ninety years old, or more. My mother had been dead five years, having lived a robust eighty-four years herself. My father had been dead more than forty years: his not a happy story, and someone I had barely known. My parents had divorced and my father had departed our lives when I was thirteen, dying a lonely alcoholic’s death twelve years later. During all of those twelve years, I spent only a few days in his company. I knew him, remembered him, hardly at all.

So of course my sister Patty’s response, answering Mr. Sabattini, was that no, my parents were not alive; so sorry to inform him. Yet as I reflected on this amazing communication, my excitement grew. I had to talk to him.

So of course my sister Patty’s response, answering Mr. Sabattini, was that no, my parents were not alive; so sorry to inform him. Yet as I reflected on this amazing communication, my excitement grew. I had to talk to him.

My mother had spoken to me a few times about the magazine crew, though I remembered few of the details. But it was a story that had always fascinated me. After she died I had thought often about writing something to commemorate her. For some reason a conventional biography didn’t appeal to me. What had piqued my imagination, too late, was the magazine crew story she had recalled during an hour and a half recorded interview I’d done with her two years before she died. Her memory of the details of that experience were unfortunately few and sketchy, with lots of gaps.

My parents had met on the crew, had a whirlwind romance and become engaged. To begin with, a happy story. Even so, my parents had been married fifteen years, and almost all of it had been tumultuous and unhappy for both of them. My father’s problem was alcohol and restlessness, in either order. There had been three children: myself, the oldest, and two younger sisters. My mother had continued on valiantly, raising us alone, my father’s well-off, distant parents more or less ignoring us. My mother had foreverafter been bitter toward both my father and his parents. While she tried to be respectful talking to us about our father, it was difficult for her, and most of her memories and conversation about him were edged with anger and mostly unfavorable.

Yet I knew also from my mother that there had been real love between them, once. And it had begun with the magazine crew; though probably those falling in love times did not much survive that adventure.

So as I read that letter from Vic Sabattini, knowing he’d be saddened that he was too late to find Ralph and Barbara, I also knew that for me this was not the end of it. Vic had thoughtfully included a phone number in his letter, and I was giddy with hope when I called him.

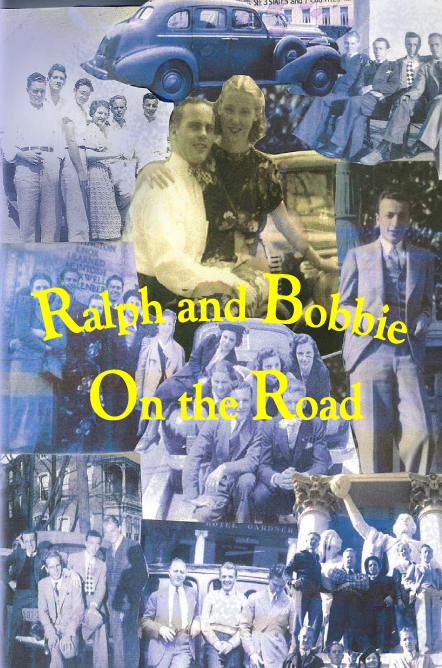

He thrilled me immediately. He laughed; he quipped; he was charming and witty, all his mental faculties fully intact and fully functioning, and he warmly welcomed me into his life. His voice was soft but articulate, and sweet with affection. He laughed easily and often. It quickly came to me as we talked that there was something elven about him. Soon we were laughing together, and when we at last spoke of the magazine crew, he laughed more heartily and said it had been one of the best times of his life. He and my father had worked with two different crews, for more than a year. They’d been best friends. He had introduced my father to my mother. He had photos.

As I listened to this sprightly voice on the telephone, I also heard another voice inside me saying: this delightful elfish man suddenly coming into my life with this wonderful story will forever be one of the greatest miracles of my life.

That first conversation lasted twenty minutes. He was overdue for his afternoon nap. He agreed to my calling again in a week, and I could interview him more thoroughly, recording it, about the magazine crew. He said that during that week he’d go look at his scrapbooks and refresh his memory. “But I warn you—my memory isn’t so good these days.” More elven laughter.

When we talked again I had rigged a tape recorder to the telephone, and had made a list of questions, trying to make sure I didn’t miss anything of what I expected to be an amazing revelation. I needn’t have worried: despite his disclaimer about his bad memory, Vic was full of details and delighted in all of them, as if it had all happened recently.

He related names and places and dates with astonishing facility. He’d recreated on paper an itinerary, month by month through their year and a half with the magazine crew, twenty or more big cities from one side of the US to the other. Late in the depression, 1937, ‘38.

Some of those stories of the past he told with much relish, but sometimes he would hesitate, seeming reluctant to elaborate further; until I realized he was being considerate of disclosing perhaps indelicate details that perhaps a son should not hear about his father. “Perhaps if you come visit. I feel awkward bringing out some of this, you know. But if you were here and asked me direct questions, then perhaps I’d feel better about answering. Some things are awfully personal. Some of the details are…awkward, you might say.”

Our conversation went on for more than an hour and my head swirled with the scenes and dramas he was presenting to me. It was even more than I had hoped for. And yes, I knew I must go visit him. When I assured him of that, he said, “My daughters will be grateful. They are sick to death of me talking about that magazine crew and will welcome someone coming here to take the heat off them.” More elven laughter.

I flew there a week later. The trailer park was the biggest one I had ever seen, home to six hundred fifty residents, all fifty-five or older. I noticed a little lake on the grounds with a big display of water spouts. Everything nicely attended to. Vic’s trailer was the only one isolated, set beside the lovely water feature. All the other trailers had been regimented together in tight clusters further away. How fortunate for Vic.

He opened the door and stood there, small and thin in white slacks and a short sleeved shirt striped in bold green. His smile was radiant and infectious. His bright eyes, and maybe something about his ears, the way his fine gray hair hid the tops of possibly pointy ears, that again made me see him elf-like. He spoke my name and stepped forward and hugged me, and that warmed me more than I’d expected. He brought me inside, his hand on my shoulder, the other employing a curl-handled cane as he walked, a little limp noticeable.

The rooms were spacious and it didn’t feel like a trailer. It was all neat as if a maid set it all right once a day. Big living room with windows all around looking at the lake and its water spouts. Two big recliners that could swivel to the view, or swivel back to the TV, each with a chair-side table. He showed me the bedrooms down a hallway: his, the master, across the hall from the other bedroom, which would be mine, which contained two twin beds, a dresser, a chair, a door to its own bathroom.

Finally he led me to a large office adjoining the living room. He’d had a long career selling life insurance. Plaques and pictures covered the walls: several of military service in World War II, certificates of civilian accomplishment, group photos from dozens of special events, newspaper articles about him, all these from all the ages of his life. And he told me of other ventures, not here commemorated. “Oh yes, the frog farm. And the Circus Hall of Fame, that was quite successful.” But the insurance had been the primary support of his blessed family, three children, eight grandchildren and twelve great-grandchildren.

“As you see in this recent photo, I am receiving a retirement commemoration from my old firm of sixty-two years loyalty, General Insurance Company. Retirement wasn’t my idea, I have to tell you. It was theirs. I just wasn’t generating enough new business to justify the cost of my office downtown. I have lots and lots of dividends still coming in from past business, but I guess that’s not enough anymore. So I’m out with them. They gave me a gold watch. I don’t know what happened to it, it’s somewhere around here. But you can see the watch in the photo there. Oh well, life goes on. I’ve only recently moved here to this park...it’s been a coupla years, and I love it here.”

Again he set his hand on my shoulder, and I realized that gesture was beginning to signify our kinship. “You know, my son, I’ve been looking around this little community here, and I see that this place is just ripe for me. The company will still let me file new policies with them, so I’ve been thinking that, what with my golf cart, which you probably saw parked out front, I can go as quick as anybody would want all over this place. It doesn’t matter the authorities took my car license away. That was strictly because of age restrictions, not because of any accident or because I can’t drive. I still can. But anyway, they got the license now, so the golf cart’s the thing. I figure I can keep selling just as much as ever, just putting around here from trailer to trailer. It’s a lotta old folks, as you can imagine. And I know just how to talk to them.”

From there he led me into the front room to an array of photos arranged in the large cubicles that also contained the TV. He picked up the foremost framed photo, an eight by ten portrait from another era: a beautiful young woman’s face shined out of it. “This is my dear Anne,” he said. “We lost her about twenty years ago. There will never be another like her. She’s still my dearest darling.” It might have been an awkward moment but Vic smiled at me and said, “We had a lifetime of wonderful happiness in the forty years we lived together. I have no regrets. Though I do miss her terribly.”

Then this man, certainly not five foot six, turned me toward the door and said, “Enough about my old life. Let’s think about something to eat. What do you like?”

I grinned, “That also reminds me to ask you a favor. I have a favorite drink I do for breakfast. I use fresh oranges and protein powder. But I forgot to buy the protein powder.”

He brightened, as if I’d spoken just what he’d wanted to hear. “Well of course! I do have a favorite orchard, since you mention it, and it would be fun to take you there. But what’s protein powder?”

Even now I could see how the warmth so quickly was there between us. Yes, I wanted this to be a successful coming together; as it was obvious Vic did also, so how could this not be full of good will between us? But there was more: slowly I was perceiving that we were in the midst of something greater than good hospitality. Some nebulous energy had taken root those first few hours, before I’d even had a chance to imagine that something like that could happen. Soon I began to see that tendrils were growing out of that root and winding around both of us, me and Vic, binding us together subtly, but more closely than I even knew. Something was happening, something so mysterious and vague that it could have no words to express it nor thoughts even to think about it. So I didn’t at first see that other dimension lurking there. Because from that first moment, it was just so comfortable and easy with the guy, like we’d known each other for a long, long time.

Before we left for the orchard he took me to the dining table at the far end of the living room and pointed at all the newspaper cut-outs, notebooks, a map and many old, small black and white photographs, arrayed randomly. I saw them and figured it might be magazine crew stuff and I got excited. I followed him to the table and he pointed to a yellowish, clipped newspaper article, some company’s name in the headline. “That’s the organization that sent out all the cars with managers, who hired the kids to go sell with them. There were two major magazine distributors in those days, and they sent out a lot of cars, and the kids sold an awful lot of magazine subscriptions, I’ll tell you. And I saw bad things—so many kids abandoned in towns all along the way, when they couldn’t sell, or caused trouble or the boss didn’t like them.” He laughed, perhaps some of it because of the astonished look on my face, as I began to see this dream of mine—finding a treasure of forever-lost information—suddenly materializing right before my eyes. “And these are some of the photos I took back in those days. All the old bunch. I guess I’ve forgotten most of their names, but hey, it’s been seventy years. But of course I didn’t forget your mother and father. I so much regret not trying to contact them sooner. And I feel especially that way about your father. He passed so young. So unfortunate. I might have helped him.”

It felt presumptuous of me to say anything in the face of the urgency I heard in his voice. Love in that urgency as well, and it touched me deeply hearing this blessing spoken on behalf of my departed father; because I had heard almost no blessings on his behalf in all my memory of him. Lots of criticism. Quite a few curses.

Probably Vic saw me nostalgic; he brought me back to myself by saying, “But let’s not start up on this magazine crew stuff just yet. If we start right now, we’ll get lost in it and miss the rest of the sunny day. An orchard you say? And what in the world is protein powder? But we’ll find it, I bet we will. And then when we get back you can make me your orange drink and I’ll tell you more about those old adventures.”

On the highway into downtown Sarasota Vic recalled a new grocery store that might possibly have my protein powder. As I drove he said, “Your father and I were best friends. We were both about twenty-one I guess, and all our lives ahead of us. Oh, I so wish I had called sooner. You know, now I’m older I see things in better perspective. That was a great time in my life. The truth is, I’ve never had a better friend than your father. I wish I had called you sooner.”

I said, “I don’t know that you would have found him very easily. Even we didn’t know where he was most of those last years. The late-fifties, early sixties.”

Vic sighed. “Yes, maybe I couldn’t have found him. I was very, very busy in my life those days. I had a family of four to keep going. Anne my wife I’d met on the magazine crew, as I told you. At one time in the sixties I was trying to do my best with the work that I was involved with in the insurance company. I was heavily involved in a business called the Circus Hall of Fame. A couple of guys and I here locally had started it in the fifties, affiliated with Ringling Brothers. That was a busy time. I was a corporation president. Then I had a frog farm to boot which required some of my time. So I was involved with three organizations at one time, and at the same time doing a four member family, so I was running all the time. I didn’t have much time to be doing other things. But I could always have squeezed in a telephone call. It just didn’t come to mind, that’s all.”

In his voice I could hear the regret at perhaps having let my father down; but I also heard regret and disappointment for his own loss here, not finding the old good buddy he’d hoped to find.

But then he laughed and the melancholy moment vanished. “Well, in all those years there were the ups and downs. The frog farm was a failure and a heartbreak. I had a full partner, Tom Ridges, and we were set to make a small fortune right there on that little patch of ground where we had our three huge holding pens. We had fifteen thousand frogs.”

There was again that little sparkle in his eye. “I tell you, son, I should be a wealthy man right now because of those frogs. Me and Tom were doing everything right. We’d started with less than a thousand frogs and had built up our collection to 15,000. I was there all the time. I kept just the right amount of water in the pens, the right temperature, checking for disease, all those things. Me and my partner had just had our big breakthrough. A fancy medical school in Maryland had just placed a trial order for one hundred frogs, and we were getting $4.25 for each one of those little fellows. In those days, medical schools were doing more and more dissecting of frogs, and we were there just at the right time. But it was not to be. Poor Tom.”

This was obviously a somber recollection; but the sudden, contrary sparkle in his eye told me he recognized something preciously everlasting in this unhappy story. “In one night our frog farm was attacked by what must have been a hundred or more river otters. It seems the big rivers there where they were living had run very low in the hottest part of summer and forced them to search somewhere else for food. I came to believe that the smell of our frog farm lured them right to us. So in one night they attacked our frog pens—a hundred or more of those river otters we figured, and the otters just went crazy. When I came over there the next morning to have my regular look at things, there was nothing but blood and guts, little pieces of frog on darn near every square foot of our property. Of course the frogs had panicked when the otters found them and lots of frogs probably tried to escape, but the otters were too much for them. Probably some of those frogs did escape. But not one whole, living frog did I find that next morning. I did find a few dead otters, who must have died from eating, or were killed by other otters fighting over the last frog. My partner Tom Ridge was so crushed by the news that he had a heart attack that very day and died.”

There was a brief silence as we drove while all these morbid and comic images settled into my consciousness. When he spoke again it was to point out local landmarks as we drove past these and out to the beach. By then he’d resumed talking about the magazine crew.

“Most of the young people that came on these crews, a lot of them were just troubled kids. For one, it was the depression when they had little or nothing at home. Some needed to get away. Others were mistreated at home and needed to get away. They had their own personal reasons, and the magazine crew gave them an opportunity to get completely away from the household. The situation where we were all on the road was just like heaven on earth for lots of them. And others, because they were raised in sort of a strict family atmosphere and they needed to get away, and they just had all kinds of reasons. Once they got away from home, why...their whole lives changed. And some of it was not...printable, for that period. But today it wouldn’t have made any difference. Now the rules are relaxed pretty much.

“Your father fit into that very easily. That life was natural to him. And at the time it was natural to me too. You know, John, this is really, when I look back on it, the starting of my sales life. I mean, my father was in the coal mines for thirty-one years, and he was also a farmer. Most all my friends from those days have worked at menial jobs, you might say. Some of them were real successes, but for the most part, I would say ninety-five percent of them were just salaried jobs, to-get-along jobs, because that’s the way they started out in the depression and they kinda stayed at that particular level. If it hadn’t been for the magazine crew that really started me out, I could have been one of those people stuck in one of those dead end jobs. Who knows what my life would have been? This magazine crew experience and what happened as a result of it gave me an opportunity to learn some really hard to learn lessons about life that helped me later to be successful, something maybe I wouldn’t have achieved if I’d stay at the same menial job all my life. You know what I mean? I learned how much I could do. On my own that is. It was a lot.”

As if he had by that speech inspired himself, he leaned close to me and said, “I know you’re anxious to hear all about the magazine crew, and I’ve sure been thinking a lot about it since you called me. So let’s get that protein powder and then get back to my house and we can go look at those pictures and I’ll tell you all about Ralph and Bobbie and me going on the road.”

ONE: BOBBIE IN BIRMINGHAM

In the spring of 1937 the most optimistic in Birmingham, Alabama, believed that the depression had at last loosened its icy grip on their lives and that sunnier, rosy times were just ahead. The revived spirit of these citizens was nurtured by the recent technological wonder of radio, and every home seemed to have one. The families listened to it as faithfully as they went to hear their preacher every Sunday. Families sat together in the living room and listened reverently and watched each others’ faces as they laughed and alarmed and cried at what they heard. Prime time evenings the networks broadcast the dramas and crimestoppers and news and a dozen great comedians. Daytime the local affiliates played all the old and the new music too, jazz and swing and blues, Benny Goodman, Kate Smith, Duke Ellington.

Barbara Bailey, soon to be nineteen, shined with optimism too, and she listened to the radio with devotion, and especially to the new music. Barbara had recently graduated high school with commendable grades, and she had subsequently been hired by Allen Brothers Emporium in Birmingham to be their cosmetics girl. They were pleased by the flattering dresses she wore when she’d interviewed, and equally by her pretty smile and her happy laughter. They put her in charge of demonstrating and telling everyone who would listen the splendor of lipstick and rouge and eye-liner, the latest thing, now available in clever little tubes just right for the smart girl’s handbag.

Barbara Bailey was everyone’s darling, a sparkly, trim, five foot two, eyes of blue, who liked to sing all the jazzy songs she heard on the radio. She usually wore her brown hair pinned back, a little wavy, all behind her ears. She’d been sent away for her own good from a troubled home in Chattanooga at twelve, to live with her strict aunt and uncle in Birmingham. The restrictions were unfortunate, but Barbara had found much to compensate her in the big city, as prosperity and hope returned, even to the impoverished south. Though the faint, foreboding shadow of a terrible war loomed, few in this lively, recuperating city saw that in the spring of 1936.

Until she’d come to this new job at the Emporium, Barbara had only sparingly used lipstick, and that only for special occasions. But her new employers encouraged her to sample all their products, and she’d come to enjoy the fun of that, the daily change she could miraculously affect upon herself with the latest this and that. She was an enthusiastic advocate. It was fun to paint up all the willing women who came to her counter every day, so curious, so many of the housewives shy of cosmetics (or makeup as the company was getting the ladies to call it). Not shy were the young girls Barbara talked to, who all liked to paint their faces.

A few of her customers each day were men, who most of them quickly bought something for a gift, embarrassed to meet her eyes (something about cosmetics reminded them of lingerie it seemed). So she was not surprised that Wednesday in the middle of the afternoon to see a young man, a few years older than herself, stop at her counter as she was laying out the newest assortment of eye-liners in the primary display by the cash register. She did notice, however, that this young man, unlike most of her other shy male customers, met her eyes confidently.

He stood holding a light jacket over his shoulder and smoked a cigarette. He said, “I’m not here to buy anything.”

Barbara smiled. “Oh, too bad. These cute little eye-liners would make your girlfriend very happy, don’t you think?”

“No, I don’t,” he said, but he smiled too. “You’re Barbara Bailey, aren’t you? I was told I’d find you here. I want to talk to you.”

She puzzled it a moment. “So who could have told you I worked here?”

“I heard about you at a party we played recently. My name’s Stan Corning. I have a swing band. We play at clubs sometimes, sometimes hotels, or parties, wherever there’s work. Last weekend at a party we played, I heard a couple of people talking, how they’d heard you sing somewhere, and that you were pretty good. I asked some questions. I tracked you down.”

Her pulse jumped and her face flushed. She set down the eye-liners. She also might laugh. For all he’d said was true, but it maybe didn’t add up the way he was adding it; although this sudden serendipity (that seemed wanting to fall in her lap) thrilled her.

She said, “Well I’m no Margaret Whiting, but I do like to sing. Especially certain songs. And I like to sing in front of a crowd. Especially when the band’s really good.” She would leave it at that, not wanting to spoil it.

Only two of these aforesaid crowds had she truly ever sung in front of. One crowd was the studio audience at Captain Henry’s Amateur Hour when it came to Birmingham, and she’d won first prize, and had thereby generated a modest high school reputation. The other had been a much larger crowd (and even more meaningless to this bandleader, Mr. Corning), in an auditorium filled by her fellow high schoolers, at graduation when she’d been asked to sing the Farewell, Graduates song. She’d sung at a few parties since then, when somebody knew how to play the piano. So she wasn’t Margaret Whiting. But she would offer Mr. Bandleader her brightest, happy girl smile, which was considerable, and let him conclude what he would.

The band leader in work denims twirled his jacket off his shoulder and draped it across his other shoulder, so agreeable, so casual, who seemed by his smile so well pleased too. He said, “Why don’t you come by this weekend at the Tutweiler Hotel on Carlyle Street, around eight o’clock. You could sing something with us. Maybe a lotta things.”

Ooolala. This would be a little dream come true. But Barbara Bailey must not appear too eager. “Well, that’s flattering. What kind of music do you play?”

“Whatever’s popular. Whatever they want.”

“That’s quite a range. Do you play any jazz? Do you have any black men in the band?”

She’d startled him a little with her sudden spunk. “We play a little jazz, the easy stuff. And yes, I’ve got two horn players who’re black. Why’d you ask?”

“Because I like jazz. And it seems the best players are usually black.”

“Oh I don’t know about that. But, say, you seem to have a lot of opinions for somebody who’s selling eye-liner.”

She laughed. “Oh yes, I’ve been around. Oh boy! I’ve been all around...I mean, around the radio dial. I listen to all the pop songs.” She laughed again. “So how could I not know everything about everything?”

He hadn’t expected her to be so much fun. He said, “So you’ll come sing with us?”

Her eyes sparkled. “Oh of course. I wouldn’t miss it.”

“You know the place? The Tutweiler?”

“I sure do. It’s where radio station WSGN does their programs Tuesday and Thursday nights. My friend June and I go down there sometimes, just to get a look inside.”

“And what song would you like to sing? I want to make sure the boys are ready for you.”

“That’s easy,” she said. “Red Sails in the Sunset.”

That evening at twilight as Barbara rode the K-Line bus back through the warehouses and smokestacks of the grimiest commercial neighborhood of Birmingham, she hummed that favorite song to herself and she calculated the advantages of her black dress with the bright floral bouquets as opposed to the plain lemon yellow with the waist jacket, a little more sophisticated, for her try-out. These were also her only choices, both of them discarded gems that she’d found in the Next To New shop downtown. From her modest salary Barbara had put a little aside each week, determined to acquire a simple but respectable working girl’s wardrobe piece by piece, even if her pay was only twenty-five cents an hour. Fortunately, it was one of her talents: she knew how to shop.

The grimy neighborhood passing continuously by the bus window, however, eventually asserted itself by reminding her that home was just the other side of this desolation. Soon she would be there and compelled to alarm Aunt Mary with her sudden good fortune. Aunt Mary of course would not see any good fortune. She would see frivolity that could hardly be Christian, and bad, possibly wicked, company, and dangerous late hours. Nonetheless, Barbara had made her truce with Aunt Mary. Now that she had graduated and was making her own money, she could go out three nights a week, till midnight, if she promised not to drink or smoke. So far, Barbara had kept her promise; though she had been seriously tempted, for the fun of it, on several recent occasions.

She wore a drab wool jacket against the evening chill, but grudgingly so, for the jacket should never be seen with the nice beige knit suit she wore beneath it. (Her only other jacket was the one for special, with the fur collar, her greatest bargain.) Off the bus, she walked resolutely to her uncomfortable moment with Aunt Mary. Her aunt was proud of her niece’s recent singing successes; but Barbara, singing regularly with a band, and spending so much time with men in a band, notoriously creatures of questionable morals–this would be another thing. Aunt Mary had never foreseen her niece’s little hobby becoming something shocking like that (though Barbara many times had happily imagined this very thing happening).

Would that her guardian might be spared this news, sure to displease. But alas, she could not be spared. Barbara turned the key to unlock the door to 442 Hiatt Street, a two-bedroom house with one bathroom, built on pier blocks, the old family home Aunt Mary had inherited twenty three years ago in a forgotten part of the town. Many poor black families lived in shanties only three blocks away. Mary’s humble little house was a modest island of relative prosperity, in the midst of hard times, for the mortgage had been paid off years before her grandfather willed it to her.

Before Barbara stepped inside she heard loud voices coming from the living room, Mary’s and Uncle Jack’s voices, and though they were energetic and disagreed, they seemed not hostile. Mary and Jack rarely argued. He worked. He let her do as she pleased at home, especially when it came to the two girls, their own daughter Carol and orphaned-out Barbara, the Chattanooga castaway. As Barbara entered the living room, that was the last word that had been spoken, by Aunt Mary, and the word still hung in the air, heavy and volatile: Chattanooga: for Barbara, a city of dark and bittersweet memories.

Barbara came into the living room and these adversaries, Mary and Jack, stood rigid and silent, he in the kitchen doorway, she standing by her rocker, both man and wife looking at her.

Mary wore one of her plain but ugly housedresses. Jack wore his denim overalls and boots. The spare furniture was old. There were a few framed photographs displayed, but no pictures on the walls. A small radio on the table was their only concession to the modern world, for Jack, with his eyes too poor to read the newspaper, loved to lay out every evening and close his tired eyes and listen to the news of the day before supper.

Uneasy, Barbara halted just inside the door and said timidly, “Am I interrupting something? I can go back outside if you need to talk privately.”

Jack shook his head at Barbara, then spoke to Mary. “You go ahead and do whatever you want. Don’t matter what I say anyway.” Then he crossed the creaking wood floor and passed Barbara without speaking to her, and went out the front door.

Mary said to her, “No, you needn’t go. Now’s as good a time as any to tell you about this. Jack’s got a nice job for the next four months in Tallahatchie. He’s got a little bungalow rented for us. I’m going to go stay with him. See some of my own folk who live down that way. I’m taking Carol.”

Barbara brightened with an implied possibility. “So I can stay here and keep a watch on the house while you’re all gone?”

Aunt Mary frowned, suppressing a righteous laugh, and blurted, “How you talk, Barbara Bailey! Over my dead body you’ll stay here four months by yourself! Not four days! Why it’s disgraceful of you to suggest it. Hah! I’d be the shame of my preacher and of every one of my parishoners if they ever heard I’d done such a thing.”

Barbara saw the iron vaulted doors of the aunt’s mind slamming shut and saw as well the fierce decree of the dictator about to drop its steely net over her. She struggled a moment to protest, even as she heard the word of doom spoken. “Chattanooga. That’s where you have to go. It’s only for four months. Then you can come back to live with us.”

Barbara groaned, a little cry of despair, for the decrees of this dictator had never, in the history as Barbara had known it, been overthrown. Feebly, Barbara spoke what she felt were her inalienable rights. “I work. I can take care of myself. I’m almost nineteen years old. I don’t need anyone taking care of me. I don’t want anyone taking care of me, either.”

Aunt Mary needed only one retort. “You’re an unmarried woman. You cannot live alone. I would never be able to show my face again in my neighborhood. And if the neighbors had any gumption, they’d refuse to have anything ever to do with you again if you ran off to live alone.”

“But Chattanooga. Would you really make me go back and live in the same house with that terrible man again?”

The lines in Mary’s face were rigid with life’s trials, all endured, and she was prepared for any nineteen year old. “I already talked to your mother Ida yesterday. She agrees with me, it’s the only way. You’ll sleep in Trixie’s bed with her. You’re always saying how much you miss your sister. And how much you miss your mother. It’ll be like a little vacation. You’ll all get to see each other again. Then, late summer, Jack and I will be back, and you can come live with us again.”

Aunt Mary had avoided the important question. Barbara repeated it again. “But...living in the same house with Fred Finch? When I talked to Momma just two months ago she said how glad she was I wasn’t around him. You know what a hard time he gives Trixie.”

Mary could not look at her for long, and she couldn’t answer truthfully. It was an unfortunate evil of the moment that must be endured. She said, “I’m sorry. I will say, your mom and I talked a little about that, and she thought she could keep a good enough rein on Fred during the short time you’d be there. As I said, you and Trixie will sleep together, and that way you can look out for each other a little.”

It had been four years since she’d lived in the house in Chattanooga, when there’d been the three of Ida’s children and the three of Fred’s all under one roof in two bedrooms, no bigger than Mary and Jack’s cramped house. Barbara remembered those scenes well when Mother Ida did not have a rein on Fred Finch, those evil nights when he came home drunk and screamed and threatened, and sometimes carried out his threats. There had been close calls that even now seemed to have been miraculous escapes. Rarely had any of these escapes been because of anything Ida had done, which had been considerable.

Mary saw a fear in Barbara’s eyes that pleaded eloquently: but Mary must not look at those eyes long, and she turned away. Barbara could only say to her, “You just don’t know how he gets. You’ve never seen him.”

Mary had had enough of this. Turning her back to go to her rocker, she spoke wearily. “Oh you’ll survive. The women always do. Just ask your mother.”

Barbara turned and went grim and silent to her bedroom. There would be no point in saying anything about singing with Stan Corning’s band.

Barbara and Carol shared the second bedroom, but little else. In the early years they had been friends, in nearly everything, when the only-child Carol had welcomed a live-in cousin. They were in the same classes. So much fun.

Carol cultivated a liberated Christian attitude, whereby she could be liberal enough to play some of Barbara’s daring games, like sneaking out the window at night to pick apples next door. And Carol could also be Christian enough to please her mother, by tattling about it. So they grew apart and snipped like sisters at each other. Mama Mary always called Carol her Good Girl. It was not long till Carol and Barbara didn’t share anymore secrets.

That night Carol was snoring on the other side of the room long before Barbara fell asleep. Barbara lay in utter darkness, curtained from the moonlit night, on the child’s bed she’d slept in since the day she’d arrived, thirteen years old, too fair and delicate a flower to leave laying about in Tennessee where a crude drunk stepfather might break or crush the flower.

All these recent years in Birmingham she’d not had to think of him much. Though the last couple years, as Trixie grew older, she had feared for her enough to have harbored a fleet of dark clouds that hovered always in the back of her mind, which would suddenly whirl up darkly and fiercely inside her whenever she thought of her sister still within Fred Finch’s reach. For the last year and a half she had been expecting a call from her mother telling her the bad news. But as yet, the call had not come. (Barbara knew also that no call didn’t mean nothing had happened yet.)

Laying perfectly still in that utter darkness, she wandered again in her mind’s eye through the Chattanooga apartment, where she’d lived most of her life. She wandered room to room; she looked at shelves and in closets; saw her old pallet on the floor in the front room, the sofa, the chairs. The one bathroom. Momma and Trixie and Buddy. And all the rest of them. Hardly room to breathe. She purposely would not imagine Fred. Even so, the dark clouds inside scudded and swirled across her mind’s eye late, late into the night.

Before work the next morning she called June and asked her to meet for lunch at Woolworth’s. They sat at the long yellowy formica counter and ate tuna fish sandwiches and sipped milk shakes. It was three in the afternoon and only half the stools were occupied. Barbara and June could see their images facing them in the immense wall mirrors behind the counter. Barbara was the most glamorous lady there in her lemony yellow dress with the matching jacket, for she had to be all day at the Emporium on stage, promoting and selling. June was taller and stouter than Barbara, but just as cheery. She wore her dark hair in a bob in back, and her dark blue dress was not as fastidious as her fashionable friend, for June was never on stage; merely a student in secretarial school, taking an afternoon break.

Barbara had briefly and sadly told June the bad news from Aunt Mary. June groaned. “No, no, Bobbie, that’s just not going to happen. You come live at our house. You know my mama will always take you in.”

Barbara looked at her own mirrored, glum expression in the face of the reversed Barbara, studying the same glum expression in her own mirrored reversed reverse. She spoke, as did the mirrored image she faced, “You know if I did go live with you, June, Aunt Mary and Uncle Jack would never speak to me again, and they’d make Momma feel like she’d given birth to a serpent, I tell you. Oh boy! After the last time Aunt Mary came and dragged me away from your place and lambasted your poor mother, I can’t believe Audrey would even let me stay once overnight again.”

June laughed. “Oh Mom got over that. It was in a good cause. But I mean it–you come live with us. Of course Momma would want you. We’ll protect you this time.”

Barbara had weighed the option many times. She had carried through on the offer three times. Each time Aunt Mary had drug her back and made her rue it.

“If I did it when she left town,” Barbara considered, “I might have a better chance. But, oh boy! Would they all ever come down on me when they did find out. To Aunt Mary, you and your momma are sinners, and you’re bent on making me a sinner too. I didn’t even dare suggest to her last night that I could go live with you.” Barbara paused and smiled to June. “She’s not a modern woman.”

June shook her head imploringly. “Someday you gotta break the bond, Bobbie. Gee–you got a good job and everything.”

Barbara brightened, remembering another, better reason to stay in Birmingham. “That isn’t all, June. You won’t believe it. The bandleader, who’s playing down at the Tutweiler this weekend, asked me to sing with the band tomorrow night. I’m gonna go, of course. But you come too. Please. I could use a friendly face; I’m already nervous as can be.”

“Oh Bobbie!–that’s great! I’d love to go with you.”

“Yes, but that’s not all. If he likes me, he wants me to sing in the band, regular.”

June shrieked. “Oh I knew this would happen to you someday! Bobbie the bobby-soxer–that’s gonna be you! Next stop–Radio City, New York.”

The other casual diners at the Woolworth’s counter might follow this lively pair without appearing to, simply by watching their doubles in the mirror. Most of them by now were doing so. Quite the cuties.

June by then had hooked the two incongruous ends of it together. “Well!—that should settle it. How can you go to Chattanooga and still play in the band?”

Barbara nodded, confounded, filled up with the puzzle. “How can I?” But even as she said that she sensed the spectre of Aunt Mary standing at the front door, arms crossed, ready to let her have it. “It’s just that Mary would think I was being so disrespectful. It would be like a betrayal to her personally. She’d never forgive me. You’ve heard her: ‘Now after all I’ve done for you, Mary Barbara...’”

June could laugh at that, she’d heard Mary say exactly that often. “No, the one I always remember best is, ‘It’s the least you could do for me, Mary Barbara, after all I’ve done for you.”

Barbara, despite herself, laughed too. “It’s funny but it hurts. I mean, I feel bad when she gets upset at me. I feel so guilty. Guilty. It feels like grease. She has done a lot for me. I do owe her. Something.”

“But not too much. Not all your waking life. You don’t owe her the rest of your life.”

Barbara sighed. “I just can’t imagine defying her. You know, walking up to her and saying, ‘No, Mary, I’m not going to do what you’re demanding I do.’ And then walking away. I can’t imagine getting away with it. She’d be furious. And she makes like it’s not really her that’s demanding I do this or that. You should hear her. ‘Jesus says you better be good. Jesus wants you to come home early. Jesus does not want you to listen to all that wild music on the radio.’”

June was vividly with her. “And Jesus does not want you to be seen with a bunch of musicians either–heavens! Oh Bobbie, this is so exciting. Let me tell Betty and she can come too. Maybe she’ll bring her new rich boyfriend Bob Phillips.”

These two girls could see in the vast mirror as their drama unwound how pleased each one was with the other. They relished their sandwiches and milk shakes, and regarded the beauty and promise of a spring morning in Dixie. There was time yet to derail the Chattanooga Choo Choo.

The Tutweiler Hotel was the new hot spot in downtown Birmingham, two blocks from the swanky Gregory Hotel, and a half block from the Sampson, which was the local music venue of renown, for they had seafood buffets till midnight when the big swing bands came through town and played there, which was often. The Tutweiler with its twenty modest rooms had only a modest restaurant, where local bands were invited to play on weekends. Though there was talk they’d soon enlarge the restaurant so people could dance after dinner.

At the restaurant entrance on the sidewalk, across from the Bank of Birmingham, had recently been installed a domed, black silk draped canopy over the entrance, The Tutweiler scripted in gold across the front of it, as if it might be a New York supperclub. Beside the opened welcoming double doors, a sandwich board waist high was proclaiming in elegant script: Stan Corning Band, Pop Favorites.

Barbara at twilight had bussed the 37 Crosstown to June’s, and the two then had taken the O-Line directly to its stop at the corner where the Tutweiler dominated half the block, and its silky domed canopy beckoned. Barbara had chosen her dark blue dress with the floral bouquets and just a little heel. She’d pinned her hair behind her ears with mother-of-pearl barrettes she’d recently bargained away from a street vendor. June wore a yellow pleated skirt, and matching yellow sweater, full in the shoulders, and white flats. World, here we come.

They could hear the band inside as they passed beneath the canopy. They greeted the smiling, come right in, tuxedoed doorman. Then Barbara whispered to June, “What bad luck–the band sounds a little like Guy Lombardo.”

The hotel dining room beneath lofty ceilings usually seated all its guests around twenty respectfully distanced tables, white linen cloaked, matching napkins, and T-embossed silverware. Tonight, with hopeful expectations, the management had crowded ten more tables among these others, and the usual crowd would have to put up with the temporary, additional intimacy. Hopefully, the music would make up for any inconvenience. Seemingly a dozen red bow-tied waiters, all in starched white shirts glided silently among so many tables, whispering their agreeable questions and readiness to serve, enthusiastically approving every choice, and hurrying on.

Barbara and June stood at the threshold. They had come here several times since graduation, but only to stand outside by the door and listen. Tonight they were official. A smiling hostess approached them, dressed far finer than Barbara even, saying, “Do you have a reservation?”

Barbara grinned and said, “No, but I’m singing with the band. This is my assistant.”

The hostess was immensely satisfied, and led them around the room’s curtained periphery to the little stage that had been recently erected in the farthest corner away from the high octane kitchen. As they came near the stage, Barbara saw Stan Corning in double breasteds and a bow-tie leading his band.

Startling away Barbara’s attention to the band was someone calling to her from two tables away.

“Bobbie! Oh Bobbie! We’re over here.” Betty waved, a blond pixie cut with a smile to match, in a fancy flouncey dress. Beside her was Bob Phillips, the most amiable of men, contriving a rich man’s arrogance for fashion, wearing unpleated and loose-fitting slacks that cost more than most of these fancy people could ever afford. His shirt was both sloppy and fine, open at the throat. Instead of any tie, as all these masculine diners wore, he wore a gray velour scarf around his neck that hung to his waist. He let his fingers play with the fringed ends, flaunting it. Betty pointed at the two other chairs on the opposite side of the table. “They’re for you–come, come sit.”

A little whirlwind of excitement spun around her head as Barbara led June toward the table offered. She glanced back to the band. She identified Stan Corning again, leading three horn players, some clarinets, and a piano, a drum and a bass, in the newest Top Ten, Harbor Lights. Oh yes. Some other harbor lights, will steal your love from me. She saw the microphone stand. Her microphone.

Barbara and June sat, but must wait briefly for Betty to relate how Bob had picked her up late in his car and how they’d gone to the wrong hotel, and then had to drive back here again. As she finished Bob hailed a passing waiter and ordered two more glasses and another bottle of the champagne. Quickly the two glasses appeared on the table. Bob gallantly stood and poured the glasses half full of champagne from their first bottle. Thereafter he debonairely sat back and let the girls talk.

But first Barbara shook her head at the drink Betty offered her. “Oh heavens no. Maybe later. But I’ve got to get this song over with.” She looked all about her. “Well, isn’t this a big crowd. I hadn’t expected so many.”

Betty continued bubbly. “This is so exciting, Bobbie. It’s all I’ve been talking about since I heard. And it’s another special occasion too, because I get to introduce you to my new steady boyfriend, Bob Phillips.”

In such a modest spotlight the bespoken would indeed lean forward and smile the most gracious smile imaginable. He held out his hand to June. “You must be June. Betty described you well. Very nice to meet you.” He might now redirect his gaze to the interesting person of the hour, this Barbara Bailey, so pretty and petite. And what else, he would see.

He could in all decorum give his hand to her as well, and he did so, straining to keep his emotional tone and enthusiasm the same as he had with the other, plainer one. “Nice to meet you too, Barbara. When do you start singing?”

The Stan Corning Band was finishing the melancholy song. Barbara stood up and said, “Right now, I hope. Don’t let any of these people laugh at me.” Barbara removed her fancy jacket with the fur collar and settled it on the chair back. She set her handbag in the seat. June nodded that she would watch it. Barbara took a breath and walked away from her friends.

Stan Corning saw her coming toward the bandstand. He smiled much brighter at her than when she’d first met him. He took her hand warmly; he said he was excited about her being there. He walked her over to the other musicians, who’d stopped playing when they’d noticed their new singer arrive. Stan introduced each man, all with big smiles to greet her, and though their names were lost to her, their good will was not. Exactly as toxic as the champagne was this excitement, as Stan led Barbara to her microphone. She reached out to caress it, and then looked out to see so many finely-dressed people, hardly any of whom now, in between numbers, were noticing the stage. Barbara’s eyes fondled her audience anyway, and she was thrilled.

Stan said to her, “OK, so you still want to do Red Sails in the Sunset?”

Barbara gulped back the joy that terrifies, and said, “Yes, I do. You mean you’re ready to go right now?”

Stan grinned. “We don’t want these folks to forget about us, now do we? Right now it is. Try out your mike.”

Stan Corning stood near, already holding his baton poised. The band behind her began to loosen up. She tapped the mike with her finger. She spoke twice timidly into it, hello, hello. Barbara heard Betty’s voice call out, “We can hear you, Bobbie. Sing it pretty.”

Before she had time to brace herself for the leap into the void, Stan Corning mercifully gave the downbeat and all eight instruments glided into a sweet harmony that quieted her soul, for it was a beautiful prelude to the lovely song she’d been singing to herself all day long. She closed her eyes. She was away. The words came out of her with a life of their own.

“Red sails in the sunset. Way out on the blue. Oh carry my loved one. Home safetly to me.” After this much the band seemed to know her and she could feel their pushing with her as she began the second chorus.

“He sailed at the dawning. All day I’ve been blue. Red sails in the sunset. I’m trusting in you.”

In this interval the band winged on without her and she turned a little to see their enthusiasm. The black saxophone player nodded and winked at her as all their horns sawed the air. She smiled at Stan Corning, who was certainly not making them sound like Guy Lombardo.

As she sang the chorus again the words felt more passionate and yearning and she let herself go with it. “Swift wings you must borrow. Make straight for the shore. We marry tomorrow. And he goes sailing no more.”

The unerring musicians carried her along. She could have sung it over and over forever.

“Red sails in the sunset. Way out on the sea. Oh carry my loved one. Home safely to me.”

And though it seemed it had hardly begun, it was over. The discreet applause was enough to wake her from her dream. She heard Betty’s more piercing hoorays and the loud clapping of both June and Betty. When Barbara looked at the audience, a timid smile broke out of her, and she bowed two or three quick times, and turned to Stan Corning. She alone heard him say, “That was very nice. And I can tell all the guys in the band liked it too. You’ve got a great feel for the song. How about doing another one with us? We’re taking a short break now, but when we come back, you come on back up. Do you know “Stars Fell on Alabama”? It’s a big favorite here.”

She glowed. “I sure do. You bet I’ll be back.”

As she stepped off the stage she felt like she floated far above the room. However, by the time she’d began walking through the maze of tables and chairs with everyone looking at her she had become timid again, and lowered her eyes till she came to her friends. As she sat the girls clapped her on the arm and held her hand and said how wonderful she was and how proud they were. Robert Phillips sat back and watched the three girls, pleased himself, and he waited, watching Barbara’s excited eyes till she also saw him.

Then he said, “That was terrific. I mean it. You were like a professional.” He insisted on the depth of his appreciation. “You should be on records. Do you have an agent?”

Barbara laughed. “Oh Lord! Aren’t you the fast talker. Do I look like I have an agent?”

“I’m her agent,” said June, laughing, giddy with the champagne, the warm spring evening, her dear Bobbie in the spotlight.

However, this was going too fast and too far for fallbehind Betty. “Well we’re all very happy for you, Bobbie. But I have good news too.” She perked to her most pixyish to emphasize the magnitude of the tale, even as she turned her happy face on Robert Phillips, her prize, and announced. “Robert has given me his fraternity pin.”

June, who knew Betty best, was surprised, and happy. “Oh, of course you’re the first one to get pinned! Oh–so it’s that serious.”

Betty pulled back her leather coat lapel to expose the silver Sigma Gamma pin, the size of a ring, without quite the commitment; yet perhaps an omen of things to come. Betty said, “Yes, it’s that serious. We met at the homecoming dance last fall. But Robert was busy at the time. He noticed me later, after the spring semester began. We’ve been inseparable since then, haven’t we, Robert dear?”

Robert dear smiled a little awkwardly, for he had been so suddenly interrupted in his discreet fascination of the moment: Bobbie across the table. But he could rally. “Yes, yes, inseparable. But you see how generous she is?–sharing me with you two pretty ladies.” Accordingly, he might look first at June, then at Barbara longer, lingering long enough for Betty to notice.

Who said, “Robert and I have even been thinking we might get married after college. We’ve been talking about it. Haven’t we, dear Robert?” She looked at him with all the devotion that was in her.

Cornered and claimed, Robert in his pride could at least answer, but without enthusiasm. “Oh well–after college. That’s a long way off.”

Barbara was in a congratulatory mood; even though this future bridegroom seemed to her terribly flirtatious. “Oh I think you two would make a great pair.”

“Yea,” cheered June, “a great pair. Let’s toast. Come on, Bobbie, drink one. It’s your night too.”

Robert Phillips must again be gallant at the unanimous call, and he filled all four glasses, that this pinning could be celebrated (even as his own neck nape crawled, viewing visions only he saw, of his own skewering and displaying: all unperceived by him yesterday in love’s blinding lights and nights). And he too could hear the song: Some other harbor lights. Will steal his love from me.

These four happy friends toasted and laughed and drank it down. Barbara must stop, however, after a sip. She set the stemmed glass down. “I’m not used to this, kids. I’ve gotta keep my head straight a little longer. Then we’ll celebrate. Oh yes we will. I’ll be right back. The band’s getting ready to start up again.”

June sent her off. “Oh you’re so famous, Bobbie. Just get going.” Robert Phillips smiled his grandest, his rosiest, for the good luck. Betty was having less and less fun, and she whispered to beau Bob that perhaps they could go somewhere, somewhere quiet, after the next song. He was not so sure. He told her they would see.

First, Barbara Bailey would sing again. Stan Corning at her side this time merely nodded once to her, like he and she did this all the time, and she smiled and nodded back. Then the band began, reeds and an alto saxophone, and then all of them rolled out with it, a nostalgic melody. Many of the diners recognized and stopped their eating to clap for it. The joy of the lyrics swelled up in Barbara. A poem to a perfect timeless moment. No broken hearts. No misunderstandings. No complications.

“We lived our little drama. We kissed in a field of white. And stars fell on Alabama last night.”

In the few previous public appearances she had enjoyed watching the audience reacting to her. But tonight, she felt too perfect, too wonderful, too much abandoned to the music. There was no need for any of that other. She closed her eyes, and she sang on.

“I can’t forget the glamour. Your eyes held a tender light. And stars fell on Alabama last night.”

Barbara stood back silent, and let the band play on without her, revolving the pretty melody and embellishing the prettiest phrases. She felt the pulse and beat of it in her, and she floated away in the spiral of the beautiful melodies.

“I never planned in my imagination. A situation so heavenly. A fairy land where no one else could enter. And in the center, just you and me, dear. My heart beat like a hammer. My arms wound around you tight. And stars fell on Alabama last night.”

Four days later Aunt Mary and Jack were packed and ready to abandon the old Birmingham homestead for a few months. Mother, father and daughter Carol had stowed all their luggage in Jack’s pickup bed and had locked the house, all the windows and the front and rear doors. They timed their departure so that they could drive Barbara and her one small suitcase to the Southern Pacific train station exactly one half hour before the 739 left for Chattanooga at 4:15 in the afternoon. Both Barbara and her suitcase, for the otherwise cramped cab, must sit atop the other luggage in the bed of the pickup. But it was a brief indignity, for they were quickly at the station.

Uncle Jack carried in her suitcase and bought the ticket for her himself. He suggested checking the suitcase, but Barbara preferred to keep it by her. It was only a four hour trip, and she’d packed only her necessaries. The Chattanooga local creeped to its stop at the loading platform at its preordained time of 4:10. Uncle Jack handed her suitcase up to Barbara, who had been all day not sociable, though not as sulky as Jack had expected. She seemed already far away. Aunt Mary and Cousin Carol waved good-bye from inside the cab, a long way off. Barbara waved and pretended to smile. Jack, a little retreating from her view as the train began moving again, also waved. Bye bye, Uncle Jack.

Barbara carried her manageable suitcase down the aisle until she came to the first empty pair of seats and she set her suitcase upon the window seat. She sat in the aisle seat and watched out the window as the train gained momentum, passing store windows and advertising businesses, and when the train began passing among small and unprosperous homes with barren yards, Barbara stood as the conductor came toward her, collecting tickets. Once he was beside her, she said, “What’s the first stop?”

The nice conductor said, “Wilmington. Thirty minutes from now. But we only stop there a couple minutes.”

Barbara shook her head. “That’s too far. I couldn’t afford the ticket back anyway. I need to get off right now.”

The conductor scoffed. “Well you can’t! The next stop’s Wilmington.”

Flustered but determined, Barbara looked around the rocking car for what she knew must be there. Her eyes saw it. She went there. She reached and pulled a cord that hung from a metal plate that read EMERGENCY ONLY. Barbara yanked. Somewhere near an alarm sounded. The train brakes gradually screeched louder until they pierced the passengers’ ears. Barbara quickly sat by her suitcase and held on.

When the train had halted, Barbara carried her suitcase quickly to the exit well, and the doors whooshed open for her. She stepped down, near an asphalt roadside that a visible street sign named Albany Avenue. A country store was open down the block. The trolley line was no doubt somewhere near. Barbara saw another conductor trotting toward her from another halted car of the train. As he passed her, she pointed and said, “The emergency’s in there,” and he hurried inside to see.

Barbara walked nonchalantly away, though she felt like skipping and whistling.

TWO: RALPH IN REXBURG

Rexburg, Idaho, in 1937 was a little island of prosperity in the midst of the recent hard times. Many of the Mormon wheat farmers in eastern Idaho harvested great homestead acreages, and though there had been little money in those recent years, there was still the land and its wealth. These farmers nurtured it and they endured the depression.

These were pioneer stock, and they had come prepared to struggle; many of them in the first years of the century, walking and riding horses and buggies overland. They had taken possession of these rolling hills in the remote west, where from the best of these wheatfields the jagged peaks of the Grand Tetons stood out monolithic and primitive and cast their own inexplicable spell over all who dwelt within the shadow of their realm.

By the late 1930s these five-acre starter farms had become thousand acre ranches and bigger. When the intense winters beset these high altitude acreages, the provident of these farmers would winter in the comfortable houses they’d built in nearby towns of lower elevations. The nearest, an hour away, was Rexburg, where many hundreds of these farmers’ families had long harbored.

Antecedents of John and Ivy Hoopes had pioneered the west and had eventually prospered, like so many of these others in the community. They were even more prudent than most. John’s grandfather had trekked with Brigham Young and the many thousand other Mormons in the great migration out of Missouri and Illinois to the Salt Lake Basin. Ivy’s great-grandmother had shipped around Cape Horn with the New York Mormons, led by Sam Brannan on the ship Brooklyn, and Ivy’s grandmother had been born in San Francisco in the same month gold was discovered by other of the Mormons at Marshall’s saw mill.

John and Ivy had four sons and a daughter. The oldest was in his last year of law school. The daughter had already been credentialed to teach, like her mother twenty-five years before. The two youngest were teenagers who spent most of their free time on the farm near Tetonia. They worked hard and they still liked to please the old man.

The middle child was Ralph, and he was a different seed. In these early years, Ralph tried to make Papa happy too, but the truth would be known: he hated farming, and he had years ago vowed he would never live another terrible winter at the farmhouse, no matter the fabulous view of the Tetons. He hated even having to winter in Rexburg. He would not of course say that in front of father John; but mother Ivy he could complain to. And he did, this one that Ivy always knew would be the prodigal, if any of hers would be.

Ivy of course it was who’d convinced John that Ralph could indeed endure the discipline of the University of Idaho in Moscow and succeed in law school, even as well as his older brother Dan. Father John was skeptical. The boy had been clever and had got through school with little effort, but he had never yet suffered any discipline. Even so, John conceded; to Ivy, not to Ralph, who could never buffalo him again. Ralph might try the student life for a year. But he had to live in the dormitory. All expenses paid. With an adequate allowance. Nothing more.

That year was not yet over. But the first semester grades were sub-par, a cause for concern but not yet alarm. It had been hoped that the mid-term grades second semester would be presentable. Alas, they were not. And worse, the failing student son had serious doubts of his own about continuing at the University, something he was very emotional about. He must come now for the weekend to Rexburg, though the highway through Whitebird Pass would be icy and dangerous still in April, to discuss his dilemma–as Ralph announced it in a carefully worded letter that he hoped would soften up the old man.

Ivy would delay the welcome home dinner till late afternoon, Ralph’s expected arrival. Ivy cooked all morning like it was Thanksgiving, making the prodigal everything he liked. John remained all morning in the living room with Dan, talking farm business and law school, purposely avoiding the kitchen. John had come by early and looked in and had seen the grand production. He was not pleased. Yet he must respectfully let her have her way, for Ivy could not in those household things be countermanded.

Even so he might lightly goad her. At the kitchen doorway John watched her kneading the bread dough. Marshmallow covered candied yams on the counter waited their bake time. The pungent sage of the baked dressing, the aroma of baking turkey. John still wore the slacks and shirt he’d worn to the deacon’s Saturday breakfast, but he had removed tie and shoes, and walked in stockings. Ivy wore a simple but ample blue housedress and a full white apron. She kept busy, even when she knew John was watching, biding his time till he could make a wisecrack that would reveal his poorly hidden displeasure.

Eventually he said, “If I’d’ve known you were going to get so fancy with this dinner, I would’ve asked a couple of the deacons to join us this afternoon. Well well, I wonder how long it’s going to take just to wash up all these kettles and bowls.”

He was only a little taller, but she seemed to make two of him. As feared as the patriarch was, Ivy, in her own righteous anger, could cower him. But this petulant remark was not worthy of her rebuke, and she continued kneading. She didn’t need to look to see he had that smart aleck smile on his face. She spoke to him still without looking up. “You are going to be the one that does the cleanup, if you’re not careful. You don’t fool me. I know why you’re doing all this smirking.”

He pretended surprise. “Not me. I’m not smirking. You don’t even look at me–how do you know if I’m smirking?”

She looked up. He was. She resumed kneading. She said, “And I don’t want you and Dan ganging up on him when he gets here. Let’s for Lord’s sake hear what he has to say, before you go off at him.”

He snorted. “What he has to say will be the same thing he always says.”

This made her frown. “Well if you don’t allow a person room to grow and change, how can you expect them to?”

Dan came from the living room to stand beside his father in the doorway. He had many times come to the kitchen that morning to peek and smell and sample. He had a gourmand’s plump belly. He wore slacks and a dress shirt without tie, like his father, though unlike his father Dan wore these fine clothes because they bespoke the man he would be, successful and looked up to.

Dan joined the fun. “Don’t you get riled up about Ralph now, Mom. Dad and I got it all figured out.”

She stopped kneading and set the plumped dough back in the crockery bowl and covered it with its gauzey cloth. She looked up at them both, smirking like Cheshires, and she shook her head. “You’re so smug it’s a disgrace. Look at you both! You set yourselves up so stubborn there’ll be no talking to either one of you. Fine help you’ll be to your brother. And your son. Ever wonder why it always ends up with nobody speaking to anybody? Well there it is.” She turned her back on them and began peeling russet potatoes that had come out of eighty pound sacks in their cellar.

John knew not to go any further with it. He backed away and Dan turned away with him, enjoying the mock hostility. The men went back to the living room. John sat on the sofa and removed his shoes, then reclined, feet stretched out, a pillow for his head upon the armrest. He faced the fine wood cabinet that housed the console radio at the sofa’s end. Dan wandered to the front window and looked through the further, fully windowed front patio. He could see all the traffic on South Third Street below, which was negligible.

John from his perch said, “You can turn on the radio if you want. Are there any good programs this afternoon? Or is it just those consarned soaps?”

Dan turned to his father and thought about it. “I don’t know much about radio daytime, except Sundays, when we all listen. I do like to listen Friday and Saturday nights, that’s really good. But I don’t know much about the daytime programs. I think it’s a lot of music. When will Gwen be home?”

“Not till this evening. It’s better that way. I want to have all this over with before she gets back from the school.”

“And the boys too?”

“They’ll be here tomorrow. They had plenty to do on the farm anyway. Oh I can’t help it, those boys are too damn impressionable right now. I see how cute they think it is when Ralph pulls some of his shenanigans. The less they see of him this weekend, the better.”

Dan puzzled it. “So we have a big fancy dinner for four of us?”

“The other half of the family’ll eat it too, later on. If I had my way it’d be wieners on a stick for everybody today, go cook ‘em up your own self. Wouldn’t my old dad have had a laugh at this? Me flunking out of school and coming home to be king for a day.”

Dan had seen this drama enacted other times. “But then you get him the next day–right, Dad?”

“Well if I do, I damn well don’t relish the job, I tell you. That’s enough. I don’t want to talk about that subject anymore.”

Dan strolled to the radio and clicked it on, but had to look closer as he turned the big dial of frequencies to the network station out of Salt Lake City, KSL.

Suddenly an unforgettable voice made its way invisibly into John and Ivy’s living room. Dan stood back from the radio console that was nearly as tall as he was, astonished. “Hey, what luck! It’s Lamont Cranston, the Shadow.” He turned to his father. “It’s a new show, everybody’s talking about it. Yea, I forgot. It’s on Saturday afternoon. But it’s so darn popular that ‘fore long it’ll be in prime time on the weekends, you wait and see. Have you heard it before?”

In truth, John liked the radio for news, especially Winchell, and little else. He had come to cherish the Sunday afternoons when all the family would be there and they could all sit around the living room and listen to their favorites and laugh and wisecrack together. But for him, having everyone together was the thing, not the radio programs, though he listened and laughed too.

He said, “Now what would I be doing Saturday afternoon sitting around listening to the radio, to some show called the Shadow? Sounds like something ridiculous.”

Dan laughed, the young man of the wider world. “Oh you have it all wrong. It’s a mystery. And this mysterious guy becomes invisible and goes out and brings in the criminals. And he scares the heck out of everybody with his voice, ‘cause they can’t see him. Pretty rooty-toot, eh?”

For a moment John listened, though he would seem not to. The voice was fascinating. Nighttime. Invisible. John looked at Dan as Lamont Cranston told the frightened woman that a demented killer was lurking in the alley not far away. He ordered her to stay where she was. He would take care of it.

Dan’s eyes widened with the thrill, and he looked at his father, to see that he was getting it too. John snickered as if it was all silly, but even so he had been caught listening. But at least it was not listening to his own dismal thoughts. Away from these he wandered with Dan down the dark alleys with the Shadow, where the cruelest of killers was reduced to a sniveling beggar by this demonic voice from the deep dark beyond that terrified him and was unassailable. John may have listened to some of the next thing, a program for teenage boys that put him to sleep; but eventually he woke up and the radio was off and Dan was at the front window saying, “Somebody’s turning up the drive, Pa.”

Somebody indeed. John roused himself off the sofa, but he didn’t need to go to the window. Ivy in the kitchen had heard Dan’s announcement and came into the dining room, wiping her hands on her apron, and said, “Now try to be civilized, you two. Let’s let the boy sit down and catch his breath before you go after him. Dinner will be ready in a half hour. See–he’s right on time, just like he said.”

Ralph’s ride home from Moscow let him out at the top of the driveway, beside the steps to the glassed-in porch. Watching him, Dan called back to his father, “He’s got his big suitcase. Looks like he brought everything home with him. That’s strange. Isn’t he here just for the weekend?”

“Lord only knows,” John said, his voice heavy with premonitions, for the clever rascal of a son was full of stressful surprises.

The shortest of all the sons, shorter by an inch even than short father John, Ralph was also lean. He came up the stairs with gusto in supple, quick movements, even with the large suitcase in one hand. He came through the porch door at the same moment Dan opened up the door from the living room to greet him there, just the two of them, on the porch.

“Well I’ll be,” Dan spoke, as Ralph set his bag down and stood to face his older brother. “don’t you look fine.”

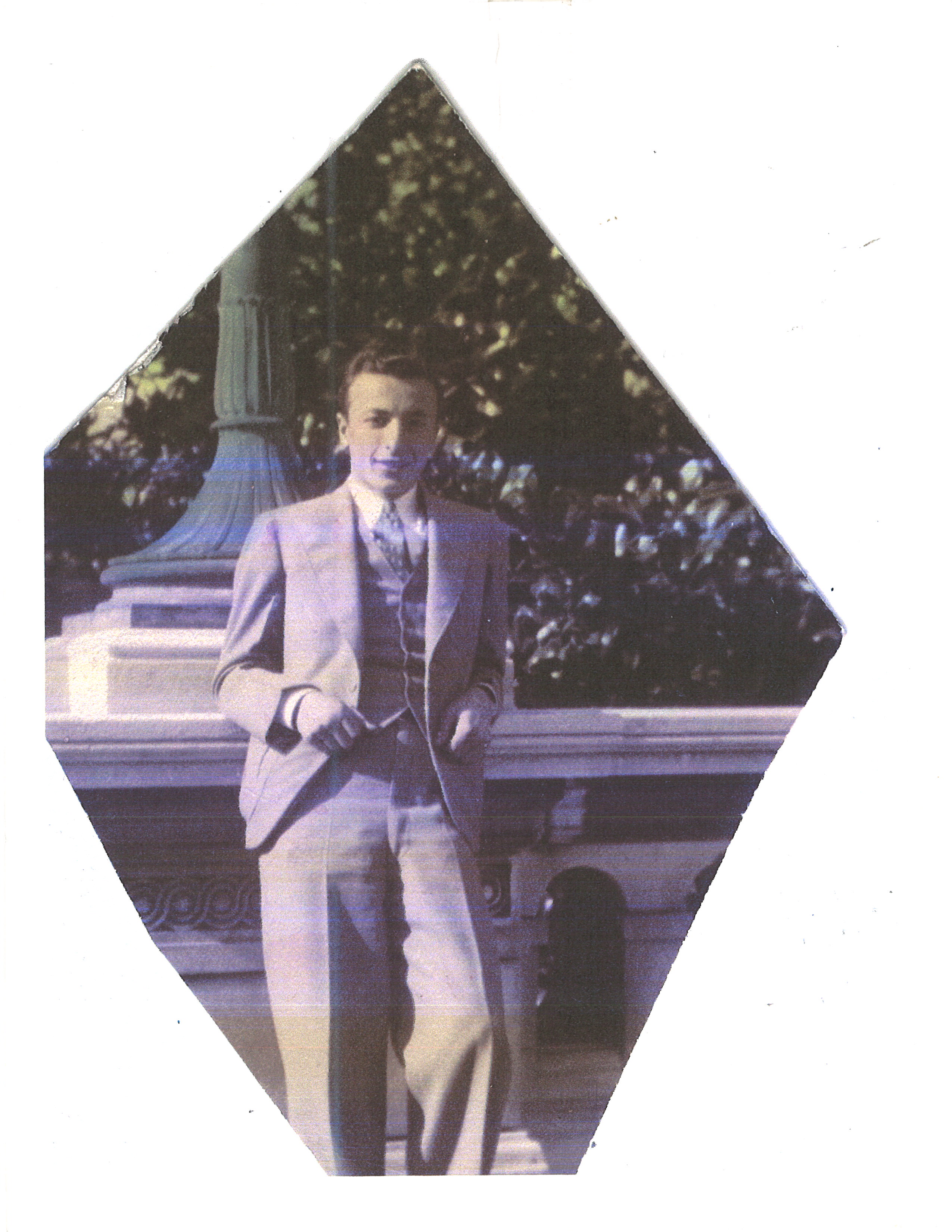

Yes he did, and it made him smile, though Ralph also knew there might not be many more smiles that day. So Ralph would let big brother stare a moment and be impressed. The conservative lawyer look of his brother was not for him. Ralph wore a pale yellow shirt, Van Heusen, with beige cuffs and open collar, to match the tan pleated slacks and light suede Jarman loafers. The dark brown suspenders were his signature detail. Ralph’s hair was light brown and wavy, combed back to expose his wide handsome forehead and his intense and secretive blue eyes, deeply set, far seeing, continually ruminating possibilities only he could calculate.

Rarely would these be drawn out of him. Certainly not today. Ralph extended his hand to his brother, showing him also a confident smile, something new, for Dan had always made the younger brother feel smaller than he already was. But the semester and a half at the University, Ralph had lived the first truly free times of his life, when neither father nor brother could inhibit him, and now he was used to an unbridled confidence. As his brother shook his hand, Ralph felt himself at least grown equal to his brother, for Ralph now knew a little of the world himself. He knew Dan lacked many qualities that Ralph now admired. Some few of those qualities Ralph had even in that short time away from home acquired himself. Ralph believed his own future limitless. Dan’s he saw now was sadly limited.

Wanting to mean it, Ralph said, “Good to see you. It’s nice to be home.” Through the lace curtains to the living room he could make out no one, for in fact John had been at the last moment pulled back into the dining room by Ivy for a last word.

Savoring the safe glide before the rapids, Ralph said to Dan, “How’s Dad?” Ralph’s tense eyes held him to an answer.

“He’s good, of course. Oh but you mean–is he already on the warpath, don’t you? Well, mama’s kept him pretty tame. For the time being. I sure hope you don’t upset him with anything. What are you bringing your big bag home for, if you just came for the weekend?”

Ralph picked up the bag so spoken. Time to move on. He said, “It’s a complicated story, Dan. Everything depends on what Dad says. He needs to see that I’m having a lot of problems up there, a lot of stress that only he can help me out of.”

“Oh boy,” said Dan, rocking back on his heels and raising his eyebrows. “This oughta be good.” He stood back into the living room to allow his errant brother to pass with his baggage into the inner sanctum. At the same moment in the dining room Ivy released John from her grip, and the patriarch came back into the living room and forced a smile for the son, whom he must remember needs room to breathe and a sense that his family is there to give him strength in difficult times, and not just constant criticism.

Ralph set his bag down again, seeing his father with a feeble smile come toward him. The son prepared himself to put his arms around the man who had been both his idol and the devil’s advocate all his life. Wishing earnestly this one evening the man would begin the inevitable negotiation perhaps some little show of sentiment, would fold his own arms around his son, however wayward that son might be. Indeed the father had been freshly instructed and he could embrace his son in a familial cordiality; and so he did; briefly; enough for both.

Ivy followed well behind, giving this a chance to have a good start, and was pleased to see them at least trying. When John and son relinquished their embrace, Ivy came forward and hugged her son robustly, for she was nearly the same height but much wider than he, and she enfolded him in her aproned amplitude.

Ralph, for the dignity he should maintain through this afternoon, must soon remove himself from any reminder of dependence, and he drew himself out of his mother’s embrace, though he still smiled warmly to her. He was a charmer. He said, “I can already smell it. You made turkey and stuffing and homemade bread. Just for me.”

“Oh no,” said John in his mischievous voice, “not for you! We’re having the President of First Rexburg Savings to dinner, to meet the good Senator from Madison County. Sam Karns from the newspaper will be here for pictures. That’s what all the hoopla of the big dinner is really about.