PROLOGUE

One September night in the middle years of his life he awoke suddenly, frightened by a dream. On a vast, dark sea he’d drifted, naked and alone on a flimsy raft, beneath an immense canopy of stars he’d never seen. Not a sound he’d heard; nor could there be any shore to this desolate ocean.

Awakened in a cold sweat, he lay in bed beside her, staring into the bedroom’s warmer darkness, waiting for the stark, sinister images to fade away. But they did not; and soon he saw that it had been not a dream, but his own weary life come to plead with him.

Before the Sun rose, he conceived that his only escape must be a blind leap into the void. Within a week he sold the business and took the money and flew away, his purpose hidden, to a fishing village in Jalisco, Mexico, on the shores of Lake Chapala. He bought a vacant lot in a residential neighborhood; simultaneously he met an honest maestro from the village, who built houses. Ajijic was faraway and picturesque; he might even write his book there, about Maximilian and Carlota.

He returned home a week later to Mill Valley, California, to Charlotte’s cottage in Blithedale Canyon. He told her everything he’d done in Mexico. She was dismayed and depressed.

Days before he’d returned from Mexico, he had prepared his apologies and persuasions, but as he stood before Charlotte, who was six feet, and taller than him by an inch and a half, she was formidable; and even moreso because she also had an indisputable grievance.

She shook her long auburn hair and would not give him anything. “This is hard, that you didn’t include me in this. It’s just shows me that your life can suddenly go a new direction, and I’m left standing here. You know I can’t accept that.”

A year ago he had gradually moved in his books and clothes, and finally given up his own apartment in Sausalito. He was surprised to hear her speak of abandoning. “Oh no! I want you to go with me. Whenever I’ve thought of this, it was us, doing it together.”

This somewhat appeased her; she surrendered to him half her resistance. Yet she was still angry. “But you should have told me. Something. Hell, it’s your business and your money, but we are at least sharing lives. Or so you say we are. But if you don’t see it that way, how can I trust you? Lake Chapala is a long ways away. And I can imagine you just running off again, after God only knows what, leaving me stranded there.”

He tried to smile her doubts away, but she didn’t accept that. He was a vagabond, and she knew he would always be. Even so, he was full of an energy she admired that moment, even while he complained: “I’m sick of all the crap I’ve been doing all these years, to keep from having an eight to five job. The crap that made me good money was too dangerous, and the crap that was respectable didn’t make any money. If I can’t see some way out of this, I think it would be the end for me.”

Still, it astonished her. “But you don’t know anything about building a house, Max. You didn’t even do that much carpentry with Ben.”

Even in the late California autumn Max wore tee shirts and levis and Y-thong sandals. His hair was thoroughly gray and grew abundantly curly over his ears. He said, “There is no carpentry in Mexico. It’s all bricks and cement and iron rebar and stones and tile. They don’t even use power tools. The only thing plugged in that I saw was a ghetto blaster. Look–we’ll watch them build our house. We’ll live in it. Then maybe we’ll sell it. And then who knows what?”

It was a pretty picture. But she had always lived in beautiful Marin County, a woman of the woods and hills and creeks, and this was much to leave. She had cats. And deer and raccoons. She pretended to weigh his proposal.

He gave her little time. “Char, you have nothing here either. Twenty-two years you’ve lived in this little place, next door to old, needy, tyrannical Isabel the invalid. It’s a nice cozy little living, but gee, Char–twenty-two years?”

She knew it. Though that argument was irrelevant, since she loved him and she would go with him no matter. Even so, she continued staring at him intently, no doubt trying to uncover something more in that face and those eyes, something he himself couldn’t help her with.

Although his eyes looked deeply into her eyes too, and he could see everything hidden in her heart. So he spoke the clearest truth he could perceive in the muddy waters inside him. “I want you to go with me. I need you. Please trust me. You know how much I care about you.”

“Alright,” she said, finally dropping her eyes away from him. “I guess that’ll have to do. But I will insist on one thing. If you’re taking me to Mexico, I want to be there for All Souls’ Day. I want to be there for one of those celebrations in the cemetery. I’ve shown you pictures.”

“You have. And that’s November first, isn’t it? We’ll have to hurry.”

And so they came down out of the north only on that first day of November, four years till millenium’s end, hoping to cross the border sometime before midnight, hoping still to find this celebration of the dead, that it might breathe new life into them and begin to dispel their California melancholia.

Charlotte for the first stretch drove the heavily freighted white Dodge Caravan as they raced ahead beneath the gray smothering sky. They brought with them twelve or fifteen boxes, a slim inventory of their lives. Three cats who were her children and family huddled unhappily in a cage in the back of the van, where she could watch them in the rearview mirror.

They crossed the border as night fell, with hardly a wave from the Mexican customs. Max thereafter drove, and he drove ahead with great caution, watching the tall weeds at the roadside for cattle and burros and dogs, calculating that Hermosillo was probably three hours ahead, if he had the energy to push it that far.

Soon the road narrowed, and they began to see battered, eaten carcasses of unrecognizable animals at the road’s edge, and signs that bid them beware of stray cattle. He strained to see into the darkness beyond headlights. By the time they came into Santa Ana, a mere seventy miles from the border, both he and Charlotte were tense and tired. He gratefully accepted her suggestion they stop there at that desolate waystation.

The clerk at Motel Elba would accept the cats, so he looked ten seconds into the room. It seemed pleasant enough. He paid the clerk. He and Charlotte brought in the cats one at a time, then a few bags and boxes. She looked carefully into the bathroom, the dresser drawers, under the bed and into the corners, and said with deflated energy, “It’s a dump.” Which of course by then he was realizing too, as he looked more closely: peeling wallpaint, broken drawer handles, old stained bedding, two little light bulbs keeping it all in merciful obscurity.

Worry not: he could see Charlotte already overcoming the squalor, going through boxes and removing her little treasures from their newspaper wraps and arranging them on the TV, on the lamp stand, over the Aztec calendar, wherever there was space. Finally she created a shrine on the dresser with three of her votive candles set in front of their bronze of three angels, which represented Larry and John for her and Ben for him, their great losses of the last two years. She placed paper flowers out of her box around them and lit the sad votives and that was it: not remotely the gay cemetery celebration she had been planning these last few weeks, but they had made it to Mexico, and on All-Souls Day, and they were indeed saying their prayers to the dead with the rest of the pagans.

1: CARLOTTA AND THE BOYS

From the day Charlotte met Alfred and Ramon they had treated her like a princess; though by then she had already come to believe it would all be like this, the great adventure of Mexico, which she had embarked on with her own Prince Max, after he had rescued her from twenty years of servitude to the crippled tyrant Isabel.

Charlotte had also been treated like royalty by the Mexican workers who had built their house, maestros and peons alike. She had cooked for them each Friday ever more elegant meals, bringing that first time pots and trays of scalloped potatoes, green beans almondine, Tuscany pot roast, hot biscuits. On subsequent Fridays she never brought the same meal twice, serving out the generous portions herself from the back of the van while Max assisted. She called them her boys. They called her Carlotta, though her name was Charlotte; and she kept the new name.

The boys had worked with great care and the house they’d built was beautiful and finished with dozens of artistic flourishes that both she and Max the artist had designed. On the last day of construction maestro Lupe had gone to the bedroom where Carlotta was crying for the end of it, and he’d begged her to come join them for the official photo Max was taking, for she was an essential part of the team.

So she’d dried her eyes and come out and joined them. In the framed photograph she foreverafter displayed over her bed they all stand proudly in front of the house, she in the middle of all, taller than any. The double-domed cupola they’d built especially for her on the housetop seemed in the photograph like a crown settled upon her head, as she smiled her pride and happiness to all the world.

That same month Alfred and Ramon had entered their lives, on the prowl for new listings. They had gushed for the house and that had won her and Max both, and they’d given them the listing. The following week Alfred and Ramon had assessed Carlotta’s sociable personality further and convinced her to train and join their sales team, despite a snide reception and frequent sniping by Polly Allen. But that happened in fairy tales too.

Even so, though visitors had gawked and praised it, weeks then months passed and the house they’d built didn’t sell. This to Carlotta had been a petite disappointment, the kind princesses are prone to. But she had borne it.

Meanwhile, she had learned the lakeside real estate business. Ninety-five percent of its traffic was Americans and Canadians, all retiring, many buying houses. Most had cashed out their lifetime equities up north and migrated to this idyllic climate, which was rarely much above or below seventy and eighty degrees. Tempering the summer heat, rains fell almost daily throughout the summer months, all so conveniently at night, accompanied by spectacular electric violence in the skies over the lake and the village. The lakeside community of gringos was more or less eight thousand. Satisfied. Taking it easy. Conservative. Old.

They were a realtor’s dream: they came, bought houses, died soon, and the houses resold. Over and over, to a continuing flow of short-lived retirees dazzled by press releases and brochures that glorified this quiet little lakeside village, where twenty thousand dark-skinned Mexicans have also lived five centuries and more.

Thus, time serenely passed for these two expatriates. Carlotta sold a few houses and brought home a few commission checks. Askance, she and Max watched Alfred and Ramon struggle to begin their own colossal project, MexicoLimpio, for as suspicioned, acquiring water permits did indeed become a problem as the lake receded further and further from the shore. Max and Carlotta would never be so ambitious. They would be happy building their one, perhaps two houses a year.

While they waited for their house to sell and while Carlotta worked for Alfred and Ramon, life was idyllic for Max in this new house they both loved so much. He searched out new exotic plants for the ever-expanding garden. He built himself a latticed pentagon gazebo flanked by royal palms with an oval, brick-lined, raised garden in front of it, full of roses. He read novels and histories and took notes on Maximilian and Carlota. His own Carlotta loved their new life. It was almost like being married.

And then the house sold, and everything changed. For better, for worse.

Three weeks after the sale Carlotta came home from the office one Friday afternoon, thrilled because she’d spotted a view lot on the day’s new listings. Nobody could have seen it yet. Five hundred meters, a perfect size and a perfect price, too good to be true. It could be their next project, and the fairy tale could resume its happy course.

They drove to the lot immediately. It was on a steep slope that might require a large foundation, who knew. But the view of the lake was spectacular and the neighborhood was upscale. And her boys could go back to work again.

Monday 9AM Max and Carlotta gave Ramon a check for ten percent down. Two weeks later the deal closed with Lionel Quevedo and his aunt, the shy widow dressed all in black, who had recently been bequeathed this property. They all signed documents. Max handed over a check for full price, and everyone shook hands. Max and Carlotta were ecstatic.

The following day Max was there on the property with Lupe and three peons clearing brush, marking boundaries and deciding where the living room would be, the master bedroom, the garage. Carlotta, who’d taken the morning off to share this special moment, was happier than she could ever remember being as she watched them all so busy, making a lot of people’s dreams come true.

She also watched a black Chevy Blazer come up the hill. It parked beside her white Dodge Caravan and a large man emerged. He seemed in his fifties, his face round, friendly, fair-skinned, more European than mestizo, wearing round wire glasses like a teacher might. However, he dressed as if he would go tromping through the African veldt, in khaki shorts, khaki jacket, and a tan safari helmet on his head. He carried a folder of papers. He smiled cordially as he walked to join them.

Mysteriously, momentously, Carlotta sensed a sudden intensifying of the air they all now breathed.

Max shook the hand this affable stranger offered, and Max greeted him in Spanish. The man introduced himself. “I am Alejandro Frances. You seem to be preparing to build, señor.” Carlotta saw in this stranger’s eyes that this was not a casual question; it seemed somehow ominous. Even so soon, she sensed grief coming. She sighed.

Oblivious to such sensitive perceptions, Max was still a proud, new landowner, smiling, eager to show off his property. “Yes we are, Señor Frances. The view is fabulous here–don’t you think so?”

Carlotta watched this gentle Mexican shift his feet nervously. “Oh, yes,” he said, “I have always thought so. But you see–this is not your property. It belongs to my family. It has been in our family for a hundred years. More than a hundred.”

Carlotta’s Spanish was not so good as Max’s, but still she knew enough to understand the essence of what this man said, and all the rest it grievously implied. She sobbed once loudly.

This startled Señor Frances. He looked at her, and must have seen the tide of loss already sweeping over her. Max stepped back, for this declaration was of course a shocking blow, and for the moment he could think of nothing to say.

He saw in Alejandro’s eyes compassion for Carlotta’s sudden sorrow, though Max also saw that this man dared not give that sentiment undue attention, lest he lose his own determination. Señor Frances turned his eyes away from Carlotta to hear Max’s response.

Max knew the words he spoke in Spanish lacked conviction, because suddenly he, as well as Carlotta, now felt the fetid breath of doom in the air all around them. “But...I have a deed, Señor Frances.”

Señor Frances nodded yes, as if he’d expected Max to say just that, and went on. “But I have the true deed, señor.” Señor Frances held up to Max the folder thick with papers. Carlotta saw Max had no heart to ask him to open it, to go ahead and prove it all to him, for he knew, as she knew, that it would all be there. But, surely, something could be done. Something. So they could still have this.

Utterly bewildered, Max barely managed to control it. He said, “Could you come with me, Señor Frances, and bring your papers? We need to talk to the broker that took this listing, that sold us this property. And to the two who say they are the former owners.”

Carlotta blanched as she recalled the forgotten players in this drama; and then she saw it all. Of course–Ramon and Alfred, Lionel, the frail, dark widow...ah yes, too good to be true.

Señor Frances bowed his head graciously, saluting them with his old world dignity, and said most patiently, “I am at your service, señor. I follow you.”

Fifteen minutes later Carlotta stomped into the Lakeside Realty office and yelled at Ramon. He insisted he was wholly sympathetic and on her side. Nonetheless, he sent them all away, prolonging their anxiety, saying that they could only meet in two days’ time, when he would bring Lionel Quevedo back to the office for the meeting. Ramon seemed unruffled by all of it. “I’m sure there’s a proper explanation,” he said with his exceptional smile, most of it for Señor Frances. “I have had other dealings with Señor Quevedo and the widow his aunt, whom he represents. I’m sure they will make this all right.”

Señor Frances thanked them all and carried his folder away with him. Ramon attempted to detain Carlotta with what he thought to her would be good news, something to lighten her burden. “Carlotta, you’ll be happy to know that, thanks to Polly Allen’s mystery ally, not only have we been granted thirty water permits, but we have also sent to Ed Bustamante a copy of our new deed from Señor Cuevas. We just today received a very substantial check from him, and we’re starting work at MexicoLimpio in two weeks, three at the most. Isn’t that wonderful?”

But he had radically misjudged her. She was fired by great anger; he had never seen her like this. “I don’t want to hear another word from you until you make good that property, Ramon! Goddamnit! You told me you’d checked the title twice! Twice!” Not waiting for Ramon to answer or Max to join her, she hurried out the door and down the front steps; she wouldn’t let them see her unraveling.

Two days later, accompanied by Max, she went to the meeting without hope. Lionel Quevedo the first time she had met him, when he had signed the sales agreement and taken their check, had seemed like a creepy little man preying on his frail, far too trusting aunt. The widow had set silently at his side, unwilling to look at documents, unwilling to look at any of the other participants. She so thoroughly trusted her thin, well dressed, sharp faced young nephew. Her check and his had been separate; perhaps and to all appearances probably a mystery to her how it had all been divided. In the end Carlotta had decided they deserved each other.

However, when Lionel sat down at the table beside Ramon, broker of the fraud, across from Señor Frances, Carlotta looked in Lionel’s shifty eyes and she wanted to strangle the little bastard where he sat. She already knew this confrontation between Lionel and Señor Frances would be no contest. She stared at Lionel, daring him to look her in the eye, surprised that he’d had the nerve even to appear. The aunt was absent of course, and probably didn’t know anything about this. And maybe never would.

Señor Frances was polite but devastating. He opened his folder and produced his documents. The first was a large map that had to be unfolded section by section until it covered the entire table. The extent of it encompassed hundreds of acres of Rancho del Oro, from the careterra to the hillcrests. Certain large areas were blocked out in blue pencil, and these he said had belonged to the family Frances for four generations. His father had recently died and bequeathed all of it to his widow, who in turn was now parceling it out among her three sons and her daughter. On top of this map, he placed a second smaller one, on which had been inscribed in thick black lines the boundaries of the property in question, which he called Section C. He traced with his finger the five sides of this Section C and said that this comprised 1480 square meters. It had never been further subdivided.

He asked permission of Lionel, who followed all this with the look of a doomed man, and Señor Frances took Lionel’s small, sad lot map and he placed this fraud upon his own great display of maps and territories. He showed them all that this little map of Lionel’s was not a true map at all, that it was only an arbitrary slice described upon a terrain to which it didn’t belong. He then produced a deed dated forty years ago in which Section C had been subdivided out of a property twelve times larger. He read for them all the metric measurements of each of the boundaries and showed that those corresponded to his map of them. He showed them the municipal seals and the signatures of notarios and registry officials for decades. His last document was yellow with age and frayed with usage and he showed them dates that were nearly a hundred years old. He pointed especially to a paragraph wherein a Jalisco governor long dead had agreed to the sale of so many hundreds of acres in Rancho del Oro to the family Frances. This deed adduced that all this property had been in its origin a quitclaim from an even more ancient deed deriving from the King of Spain nearly two centuries ago.

As Señor Frances finished and looked up at the others, he nervously wiped little traces of sweat from his brow, then sat back in his chair, waiting for someone to say that what he’d said could not be true. But no one did.

Max turned to Lionel, whose squinting eyes were still creeping from map to map and deed to deed. Lionel shifted uneasily in his chair when Max said to him in Spanish, “What do you say, amigo? What does your aunt say, the widow?”

Speechless, Lionel at last looked into Max’s eyes, since it was the least of payments he could make. However, he could not bear the confrontation long, and his eyes slid away, dipping and floating helplessly. Carlotta could see that someone else might pity those desperate eyes, but not she: who watched him rigid with anger.

Finally Lionel spoke in genteel Spanish, but meekly. “Yes, there is a possibility I have somehow mistaken. My engineer took measurements from a certain reference marker that may not have been the correct marker. I suppose that is possible. My property is part of an inheritance my aunt received this year, from her husband. She meant only to sell it. Her deed comes originally from her father-in-law. Though I see there is no doubt that the documents of Señor Frances are in good order.”

Max then turned to Ramon. Before Max spoke, however, Ramon was ready with an answer, trying to smile through his own obvious bewilderment. “I did check it, I swear, but I checked the deed only, not the map. And not the location. I never imagined, if the deed was correct—and the records showed it was correct—that the location would not be what the map shows.”

Hearing this, Carlotta slumped, drained of all hope. She said bleakly, “What do we do now, Ramon?” Who in her opinion deserved the shotgun, along with his rascal confederate, Lionel.

But Ramon was already having ideas. Suddenly he perked. His smile blossomed like a merry poppy at a wake. “Let me offer this! The lot in question does exist–I’m sure of that. If Lionel has mislocated it, he can make another survey with greater care, with a new engineer. He may use the man we use, Señor Guacho, and establish the true location. It should not be a problem.” And to Lionel he said, “You could do this–yes?”

Lionel, sensing a miraculous reprieve, struggled to look optimistic, struggled to make a strong affirmation, desperate for any solution which would allow him to walk away unfettered from this meeting. However he could only mutter a twist of words that no one comprehended, though all believed he was probably trying to say something affirmative.

At the boiling point, Max spoke to Lionel, who tried to wipe the sweat from his forehead with a gesture that would keep its purpose hidden. “And what if I don’t like this other lot? Wherever it turns out to be. What if I want my money back?”

Carlotta had already forsaken any hope of that.

Lionel attempted to smile sympathetically but his mouth quivered and could form no such smile. He could only say, “That’s not possible I’m afraid. The money’s gone.”

Max, not surprised, pressed further. “What about your aunt’s money?”

“Gone also. But please, no need to talk of money given back. I’m sure the lot in question must be close to the other on that hillside, and all the properties there have beautiful views.”

Max strained to keep it simple and direct. “But you’re not hearing me. What if I don’t like this new location? What if I don’t?”

Ramon raised his open hand off the table in a gesture that asked for their attention. He said, “Let me make a suggestion. We should hold off any discussion of money being given back until we know where the actual property is located. Who knows?–there is even the possibility– considering it’s in Rancho del Oro–that the property will be–Finer!–than the one you thought you’d purchased.” He glowed with optimism.

“Or it could be way worse,” Carlotta said, for she had seen plenty of that kind too, even in Rancho del Oro. Her hand covered her eyes, drowning in dejection.

“We shouldn’t be thinking negatively,” said Ramon, refusing to look at her. “Please, let’s take this one step at a time. Let’s give Lionel’s new engineer a chance to locate the real property. And then we can talk about what we have, or don’t have. Isn’t that reasonable?”

Max stared hard at Ramon and said, “Reasonable or not is something else. But I’ll tell you–I’m damned unhappy about this.” Max turned to stare as hard at Lionel, who could barely return his look, and Max said, “And that goes for you too.”

Max turned to Alejandro Frances who sat next to him. Señor Frances had during all this kept his eyes respectfully downcast, graciously not wishing to call down by his own witnessing any greater shame on those responsible. The anger but not the agitation passed from Max’s face and he said in Spanish to the land baron Frances, “I’m sorry for the trouble we’ve caused you, Señor Frances. I see the property is yours. My men will stop working there.”

Señor Frances smiled at him so large with gratitude that Max was surprised and silenced from saying anything further. Señor Frances answered in the same language, “You are very kind, señor. I appreciate your honesty very, very much.” Then he folded his maps and deeds again to their portable sizes and placed them one by one back in his folder. Ready to leave he said to Max, “I wish you luck finding your property. If I may be of any assistance, please call me. Here is my number, I am at your service.” He handed him a card. He looked to the others as well and said, “And if I may be of assistance to any of you, please call me as well.”

“Oh yes, yes,” said Ramon, who was assisting Lionel to rise, who was happy he was out on his own recognizance. Confident Ramon spoke for his crippled accomplice: “And rest assured, all this will be resolved to everyone’s satisfaction.” He flashed them once more the handsome smile that he had ready for the quick getaway, and he ushered Lionel away.

Señor Frances rose to leave and wished Max and Carlotta well again, and thanked them for resolving the problem so graciously. “It does not always happen so, Señor Max, Señora Carlotta. And for that I thank you. My family thanks you.” And he departed.

Carlotta again covered her eyes with her hand and Max could not hear her crying; but he saw the steady rise and fall of her chest and he knew she hid her tears and he knew how complete was her misery.

Nothing really changed for weeks. Lionel and his new engineer week to week passed on to Ramon little maps that they’d told him were each probable locations of the disputed lot. Ramon likewise passed these on to Max and Carlotta, with smiles more and more feeble. Finally Max and Carlotta gave all their documents to a Mexican lawyer named Carmelo Delavaca of Chapala, a man thin and sleek, always in the best suits, a little moustache, a charming grin, who accepted their retainer and promised swift and certain justice. He assured them he had what was most important of all, the good connections.

Nonetheless, Max and Carlotta came to accept that the property was lost, though the money might be recovered. Max, however, admitted one last desperate strategy. He and Señor Frances met at a little sidewalk coffee shop in downtown Chapala where Max had invited him, prepared to be even extravagant in his offer to buy all of Section C.

As they sipped their coffees, however, Señor Frances told him it was no use, that the family soon would begin developing the property. Brother Federigo was an architect. Then he’d shown Max a surprising smile which Max had thought of as elven, for Alejandro’s eyes suddenly sparkled when he said, “My father told me and my brothers, many, many times–never sell, only develop. My father said there is only one thing worse than selling undeveloped property.” He winked. “But he never told us what that one thing was.”

Then he became again merely sympathetic and laid his arm across Max’s shoulders. “I understand how you feel and I truly wish I could help you. If it were only up to me, I might. But this selling land is a thing that always involves the entire family. You understand.”

Carlotta sighed and began looking again half-heartedly through each day’s new listings. A week more passed. Polly and Alfred were spending more and more afternoons at the big Cuevas property doing MexicoLimpio. Ramon was in Guadalajara again, doing who knew what, and it was left for Carlotta one Friday afternoon to close up the office. She afterward went to meet Max in the plaza for their twice a week lounge on the iron park benches in the village community living room, where they watched the locals come and go and sit and gossip.

Carlotta went up the little steps to the plaza and saw there were only a dozen or more Mexicans strolling the plaza or sitting. She saw Max on an iron bench, sitting beside Alejandro Frances. She sighed again remembering the beautiful property that wouldn’t be. Both men were laughing as they watched a little boy playing with an empty coke can. Max saw her and waved. She saw another man, perhaps another of the Frances brothers, on the bench next to Max.

Alejandro rose and made her the smile that already had endeared him to her. At the same time Max also rose, hugged her briefly and turned her toward the new Frances and said, “This is Oskar, Alejandro’s brother.” He rose to greet her; he too had the generous family smile. But unlike Alejandro’s conservative gray slacks and open-collared business shirt, Oskar wore levis and a bright short-sleeve with sunsets and palms waving. He seemed younger than his brother, though not much. They both had the identical bald head, the same long wispy hair sweeping left to right across the dome.

The men reseated, making room for her, but she preferred to stand. Alejandro spoke to her in a slow, calculated English, the first time she’d heard him use her language. “Good to see you again, señora. So pretty you look—Que bonita—as we say in our language.”

“Yes,” said jovial Oskar, in English no more polished than his brother’s, “you are ready to go to dinner with the mayor.”

She laughed, believing it was the new hair color. “I dress this way to sell more houses. It’s what the gringos like.” She saw it amused them that she’d used that word.

Alejandro said, “Max is telling me that you have still not discovered your mystery lot.”

She laughed again, that he’d found in English such a perfect word to describe it. “Yes–our mystery lot! I laugh, but I’m still angry. A lawyer is helping us. I hope he’s helping.” She hesitated, then decided to say it.

“Ramon is making us deal with Lionel on our own. Says he can’t waste any more time on this because it’s not resolving quickly. He won’t talk about giving back his commission either.” She stopped talking, took a deep breath, and tried to reassert her smile of a moment ago. She wouldn’t look at Max.

“Disgraceful,” spoke Alejandro shaking his head. “Unfortunately. I have seen this before in these real estate people. I never use them.”

“Fine,” Max said, surprising her to hear a lilt of humor in his voice. “We’ll sue Ramon too, along with Lionel and the widow.”

“Go ahead,” she responded with an avenging grin, “I wouldn’t care. I’m ready to quit.”

Alejandro placed his big hand on Max’s shoulder and said, “Let me speak to my brother Federigo. He is very resourceful, perhaps something can be done to help. I will call you in a few days.” They spoke a few minutes longer, but nothing that seemed memorable. Then the two brothers wandered away.

However, two days later Alejandro telephoned. Max at five minutes before eight in the morning had to take the call in the bedroom, naked and dripping from the shower as he tried to dry himself one-handed with a towel. Alejandro told him that the brothers had conferred and had agreed to sell them Section C. Brother Oskar in addition possessed a piece even bigger than Section C on Rio Bravo, though with a lesser view, but still very desirable. He would also sell that, well priced, if they wished it.

Carlotta stood beside him bouncing on her toes as she listened, knowing by some psychic osmosis exactly what was transpiring. When he put down the phone, his face stricken with astonishment, she shrieked for joy and couldn’t have stopped herself.

That same day they met Alejandro at brother Oskar’s village apartment to sign the sales agreement and to give the brothers the ten percent down. Two hours later they met with an accountant named Jesus Calzon, who explained to them the procedures for incorporation, and they signed the appropriate documents and they paid him his fees. Then Carlotta went four hours late to work and gave Ramon her notice to quit, thinly masking her gloat with a smile that was worthy of Ramon himself.

2: CELEBRATION AT THE POSADA

Only after all this momentous work was done did Max and Carlotta make their reservations for that night at the Nueva Posada to celebrate. After a year and a half of Mexico, and especially the anxiety of the last few months, it was suddenly all perfect again, the fairy tale resumed. They had signed their names together so many times that day on so many official documents that she almost felt married to this man she had followed with so much trepidation to this corner of the universe. And what had they done? So little and so much. They’d watched the boys build a house. They’d sold it. Today they’d made themselves a legal corporation. Bellacasa they’d be called. They would build beautiful houses.

Their table that sparkling spring night at the fabulous Posada was at the end of the patio nearest the garden, where the light was dim. They sat with their backs to the four or five other occupied tables. The garden was full of flowers. Two old men with painted guitars wandered from table to table of the dining room inside the hotel, their romantic old songs carrying out through the open doors. The ancient rubber tree spread a dense canopy high above Max and Carlotta. When the guitars paused between songs, she could hear the hush of the waves sliding up the shore far beyond the garden wall. Max poured the red wine. He said all the right things, in just the right tone of voice. He was capable of all of it. Even that one tiny regret, even that might be made right on a night like this.

As they looked into the starry sky above the lake their heads almost touched. He asked, knowing the question would please her, “You know we’re almost broke now, don’t you?”

She glowed. “Yes. We don’t have enough money to build a house on any of those seven new lots we own.”

He was as happy as she. “Our future clients will give us money to build there. Would you like to go to Paris?”

They looked and smiled into each other’s eyes. She could see he would like to make it all true. “If you took me to Paris you’d never have to do another thing in the world for me. Not ever.”

“Then we’ll go to Paris.”

Yes, a perfect night, a perfect moment, fit for a princess. The guitars faraway started up again, a melancholy Lake Chapala serenade.

Yet all this was suddenly overcome by a nasal-toned human trumpet blaring Max’s and Carlotta’s names across the patio. There was only one source for it: Morley, the patriarch of the Eager family, who had ten years ago built this finest showplace in all Ajijic, a five-star eightteen room hotel, restaurant and bar. Today at seventy years old Morley was only a hobbling parody of the man who had so delighted women of all types and ages for much of the twenty-five years of his residence in the village, delighted their men as well. Now he was flamboyant only by his still piercing wit, his piercing voice and his flagrantly uninhibited use of both. Delighted, Carlotta turned to greet him.

Malcolm was beside him, Morley’s only slightly younger sidekick, dressed as always in shorts and white knee-length socks, flaunting a trim waist, gray wispy hair on his head, and the usual grin on his round rosy face that reminded Carlotta of what a hobbit must look like. Morley limped, though elegantly, to their table, only sometimes using his cherrywood cane. Max stood to shake both their hands and offer them a seat, equally delighted, saying, “Yes, come sit with us. This is nothing private. We’re just celebrating.” She might have slapped him if they’d been alone.

Morley leaned down to kiss Carlotta’s cheek as she said, “So good to see you, Morley.” Then he stood and leaned sassily on his cane, and with his free hand stroked one end of his long moustache. He said, “You’d be surprised, dear, how few women these days let me get that close. I appreciate your confidence in me. Malcolm and I have been hitting all the bars on the plaza. Seeing who goes there.”

“Speak for yourself, you old rascal,” said Malcolm laughing. Then he too leaned down to kiss Carlotta. “We’re not interrupting anything intimate, are we?” he asked in his hobbitish Boston brogue. “I ask, because Morley wouldn’t know to ask.”

“And wouldn’t care,” Morley added. “Because if it’s intimate, I want to be there. Group intimacy is the best kind.”

Malcolm laughed and defied him. “Jesus, Morley, you’re not fooling anybody–they only let you loose once a year.”

A sly grin lit Morley’s face. He looked first at Max, then Carlotta, before he turned back to Malcolm. “Yeah, but that once a year I take no prisoners.” Morley set his hand on Max’s shoulder a moment, to acknowledge Max’s appreciative laugh, and said, “No, I can’t stop and socialize, but Malcolm will–I’ve got to report in to my wife.” He winked. Then Morley limped away toward the big doors, looking to either side of him as he prowled among his unsuspecting diner guests.

Malcolm noticed someone he knew at a table two removed from them. “Say there, Kraburn, I thought you’d gone back to Florida.” Malcolm walked toward him.

Casually dressed Kraburn eased back an empty chair, inviting him to sit. Malcolm instead stood beside him and said, “Say, do you know Max and Carlotta there? Maybe we could all push our tables together, get to know each other. Max and Carlotta like to build houses.”

Kraburn said, “I know.” He turned to look at the couple, and nodded respectfully. “I’ve heard people talk about you.”

Carlotta looked closer at this man. He seemed faintly familiar. Where? This Mr. Kraburn had dark, wavy hair, bleached at the temples and on the fringe of the wave that looped his forehead. His face was ruddy, but not from sun. He wore an expensive, loose white sweater, red stripes around the wrists, and dark denim shorts. His long, hairy legs he extended off the side of the table, one sandaled foot cocked on a knobby knee. A modest pot belly. He was probably six feet three or four. Probably mid-fifties. Rugged. Carlotta thought he looked like a drifter, but one who had enough money to keep himself comfortable. Some women would think him appealing; she imagined it would be the ones who were willing to let him do most of the talking.

Half to Malcolm, half to Max and Carlotta, Kraburn said, “Didn’t go back to Florida. Still looking for the right house. Or the right place to build one. So far no luck.” Then he gave all his attention to Max and Carlotta. “So you two have a few lots for sale–huh? I couldn’t help overhearing.”

At that moment the head waiter Armando, in the same creased black slacks and ruffled shirt and magenta cummerbund that all these waiters wore, came striding across the patio, grinning like the wish-granting genie he was. He bore on his fingertips a silver tray and a bottle of wine upon it, and he set all this on the table before Max and Carlotta, who were visibly surprised.

“This, Señor Max and Señora Carlotta,” he said grandly, “is a gift from your amigos at the table over there.” He indicated with a flourish of his hand a table near the door. Carlotta looked closely, then took a deep, restorative breath when she saw Ramon’s teeth smiling at her, his little delicate hand waving hello. Polly Allen sat next to him, unable to smile, but making a little wave of her chubby hand.

Strangling her spite, Carlotta waved back feebly and mouthed to her benefactor so distinctly the words Thank You.

But in that instant she suddenly remembered that forgotten morning in the office a week ago, Ramon showing this Mr. Kraburn the drawings of MexicoLimpio, and she wilted.

“Oh Christ!” she said discreetly to Max. “Ramon thinks he’s caught me stealing his goddamn client Kraburn!” Then she saw that even the bottle of wine would not be gift enough, for Ramon himself rose effusive from his table and launched himself across the patio toward her like a happy missile.

“Oh the little love birds,” he twittered and chirped when he came near. That sentimental speech seemed to brake him sufficiently so that he could glide without actually stopping his motion into the seat that Max had pulled out previously for Malcolm. Ramon settled in adroitly. With a flourish he smoothed the front of his silk heliotrope shirt and poised his elbows onto the table so that he could lean confidentially toward them. His gorgeous smile was for them alone.

Mr. Kraburn in the meantime had drawn back his chair, relinquishing the floor to him who could not be upstaged.

“I hope you like the wine,” Ramon enthused, “it’s for several reasons. A going away present for you, dear Carlotta, just so you know there are no hard feelings. At least on my part. Secondly, I want to congratulate you on your very impressive acquisitions today.”

Carlotta gulped. “How do you know anything about that, Ramon?”

His smile quickly softened. “Oh I find out things. You should know that by now. But how doesn’t matter–now does it? It’ll be public record in a day or two anyway. So I congratulate you–these Frances brothers are quite the catch! Oh I knew we couldn’t hold on to you long, Carlotta. I’ve always been sure that you and your prince of a husband would do great things.”

Then Ramon looked to Mr. Kraburn, who was watching all of this intently, and Ramon extended a generous arm to him as well, saying, “Why Mr. Kraburn, I see you’re getting acquainted with my former star salesman Carlotta and her husband Max. They’ll soon to be our newest tycoons—I believe that’s the American word.”

This recalled to Carlotta her embarrassment of the moment before. “Look, Ramon–I’ve not even said one word to Mr. Kraburn–he just introduced himself. We haven’t said a word about business–I don’t know anything about anything.”

Nothing could have delighted Ramon more. He squealed. “Oh dear, dear Carlotta–no, no!– it’s you who misunderstand. Mr. Kraburn is my other gift to you. He’s looking to build, but walled-in communities are not for him. I recommended you to him. He and I talked in the office recently, I believe you were there, and he’s just not the type for MexicoLimpio. He’s another kind of rare bird. Aren’t you, Mr. Kraburn?”

Mr. Kraburn seemed flattered by the description and moved his chair once again a little toward them. He spoke now with a clever smile. “The question is, Ramon–which rare bird.” He probed his shirt pocket for a thin panatella and lit it with a chrome lighter, a USMC shield affixed to its face. He did it all without taking his eyes off his two interesting new friends, the builders. Malcolm had settled in a chair at the far side of Kraburn’s table and was allowing them their business talk, though he watched them with obvious interest.

Master of ceremonies Ramon had apparently finished his work. He stood and quickly surveyed them all, a little patchwork family now. He leaned and spoke so only Carlotta could hear. “I expect full commission on Kraburn, my dear.” Then he stood clear, and spoke so anyone might hear. “And I do hope you solve the puzzle of your mystery lot. That has been so much distressing me. But I’m sure you know that.”

Max’s smile was a dare. “OK–then show us how distressed—give back your commission.”

Ramon’s explosive laugh blew all of that away.

Carlotta felt Max beneath the table step on her toes. She squirmed her foot loose. Then Max suddenly said something that surprised her–not for the truth of the statement itself, with which she would’ve agreed; but it surprised her that he would confess the truth to their adversary in this.

“You know, Ramon, if the price we pay for knowing the Frances brothers is to get screwed by Lionel, then so be it, I’ll take the trade.”

Ramon glowed his brightest, as if nothing in that moment could have pleased him more, and so it might have been. “Oh that is so generous of you to say, Max. I love that about you, your generosity. And yet, you know, it is just what I have been thinking myself recently—a fair trade!” He laughed a little too much in their faces, and he seemed a moment later to sense it, for he then looked toward Polly Allen, who sat still at their table looking at them all with no visible emotion.

Ramon let his gleeful laugh overflow and flood in Polly’s direction, no doubt that she might see how he could walk into the lion’s den and laugh at the lions, and then turn and walk away. For so he did, feeling no need to say farewell, merely turning as he laughed, and then walking away, the sweetness of his laughter trailing behind him like a matador’s cape.

“Good God!” said Carlotta, “I feel like I’ve just been slobbered on by a fucking Saint Bernard! And why did you let him off the hook like that?”

Max smirked. “I feel generous tonight.” Then he looked to Kraburn, smiled and said, “Come join us. You too, Malcolm, let’s drink this wine, though it might turn out to be vinegar.”

Carlotta saw it might be their last private moment and she leaned to Max and said quietly, “What’s happening to our night out?”

Kraburn would leave them none of it. He stood, bigger even than he seemed stretched out in his chair, and then he resat himself in the chair Ramon had vacated. Malcolm drew his own chair to the table beside Kraburn and accepted the panatella Kraburn offered. He accepted from him as well a light, and said to him between puffs, “Max’s writing a book, too. He’s a man of multiple talents.”

Kraburn said, “Oh?” and might or might not have been genuinely interested.

“How’s that coming?” Malcolm prompted the author.

Max poured a glass from Ramon’s bottle for each one. “Slowly. Ten pages or so a week.”

“He’s writing a novel about Maximilian and Carlota–it is a novel, isn’t it, Max?–you’re not doing something factual, are you?”

Max tasted from his own glass and smiled, then put it down. “No, nothing factual. Based on fact. But it’s actually fantasy. You know, everyone laughs at Maximilian because he’s such a mad idealist, but what if he’d really had the full support of the Mexican people, the church and the Mexican military? Maybe he’d been able to make a lot of those ideals come true, and then what would Mexico be like now? I think he could’ve made Mexico healthy, maybe even a strong country, an equal to the United States before he was through. But everything was against him. And he was doomed.”

Kraburn seemed to follow all this. Carlotta sat back in her chair, enjoying not having to push the business, as if none of it were more important than this little conversation about Max’s literary hobby.

“So this will be, like, something that never actually happened?” asked Kraburn.

“That’s right,” said Max, “a what-if. I never really liked the way Maximilian and Carlota’s story ended. A total disaster. It’s not even tragic, it’s just senseless. It’s almost comic. At least that’s the way I read it. I had an urge to rewrite it, make it end like it should have ended. So yes, it’s a what-if.”

“Yeah,” interjected Malcolm, again a hobbit, “and what if Maximilian and Carlota hadn’t had their heads up their asses and they’d actually seen what was going on all around them, right in front of them, which they should have, right from the start? All that opposition. That subterfuge. What if that?”

Max laughed. “Well, yes, that’s true too. But that’s another story. Maybe it’ll be part of my story, who knows.” Then he looked at Kraburn, and offered what seemed a more frivolous topic. “So, you’re looking to build a house.”

Kraburn sat forward, setting one big hand on his knobbed knees and with the other withdrawing the panatella from between his clenched teeth. He said, “Yes I do. The lot doesn’t have to be big. I want a nice view. A super view would be better. And I want a builder I can work with, so I can incorporate some of my own ideas.”

“You married?” Max asked, like an interviewer with a significant question.

“Not really.”

Then Max thought of another, equally significant, or not. “And did somebody say you’re from Florida?”

“Yeah. Key West. I gotta boat.”

Malcolm snorted. “You won’t need it here!”

Kraburn seemed to miss the joke, or he was thinking about something else. He said, “So–what did you do before Mexico, Max? Construction, I suppose.” Carlotta sensed that he supposed nothing like that.

Max smiled pleasantly. Carlotta knew Max would not be enjoying this turn to the conversation; though he would be prepared. Max said, “Yeah, construction. Though mostly it was remodeling. And I was a salesman.” Only she knew that these were partial truths, that he’d omitted a world of significance. Then Max slipped away from Kraburn’s question with one of his own. “And how about you?”

Kraburn seemed happy Max had asked him. “Oh I was in special services in the war. Couldn’t ever talk much about it, top secret stuff. Still is. I was leader of an assault team in the Marines.” He looked away, and Carlotta was sure he was enjoying the effect his resume must be making on them.

A moment later Kraburn turned back again and said, like a crafty CEO might look at a sadly under-qualified applicant. “I’ve already researched your company. There wasn’t much. I know you’re the new kid in town, that you don’t have a lot of experience. But I might be willing to go with you, despite that. I like your enthusiasm, and you seem willing to listen to other ideas.” Then he winked, and it might have been for fun, or maybe it was for something else only he knew. Carlotta thought he spoke the next a little too intensely. “I know you’ll let me have what I want.” It made her shiver.

“OK,” said Max, “what say we go look at a property we have that just might be what you’re looking for. Say tomorrow?”

They agreed. Carlotta saw a capture. Of a dangerous animal.

Only a few moments later Carlotta convinced Max to say goodbye so she could take him outside. As they paid their bill, Carlotta said to Max, “Frankly, the guy makes me a little nervous. How do you think it’ll be working with him?”

He smiled at her and spoke the truth as he knew it. “What do I know? We sign a contract. He gives us a big down. What could go wrong? We’ll modify the house plans we used on the Chula Vista house, that was a good one. We’ll probably need a little more foundation I guess, but no big deal I suppose. I’m sure Judy Tovar could help us work in the changes Kraburn wants. She’ll be doing the final plans anyway.”

Carlotta could accept that. Despite all the snags, here they were, dreams coming true, and it still felt to her like the wind was at their backs. They walked away from the Nueva Posada, first on the cobblestoned street, then on sand, where she removed her sandals. No moonlight was on the lake, but even so the foamcrests of waves were bright, rolling across the beach just ahead. Taller than he, she laid her head on his shoulder when they slowed to admire the bright cluster of lights on the faraway shore that was the pueblo rustico of San Luis Soyatlan, and the lesser cluster further east, Tuxcueca. The lake separating them from these lights lay black and still, to dull eyes invisible in the bigger darkness.

But at last the Moon rose, a little past fullness, illuminating for them a huge tide of lirio that in its aggregate passing had settled tonight along this shore. Because of this clog of moonlit lirio no waves or water lapped the sand beach; only bobbing, flowerless water lilies gently pushed forward, then sagged back, to indicate the baffled pulse of the lake.

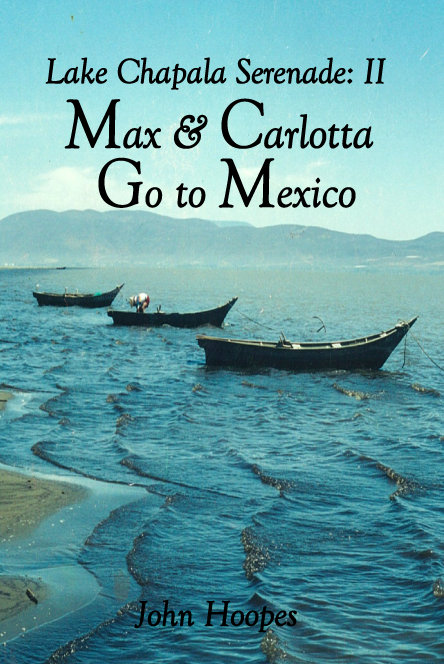

Carlotta and Max halted where a fishing boat had been staked among all this vegetation, tied by several meters of rope to a tall iron spike anchored in the sand. The boat was of the kind they saw everywhere along the shore west of the village, anchored like this one. Like this also were those rowed slowly by one or two fishermen in the cool mornings upon the lake, who played out long handfuls of net behind them to capture the lake carp or the tiny white charales that swarmed in these shallow waters.

All these boats were made by hand of rough planks nailed to stout branches, chosen for the perfect angle of their branching. Upon these branches, the planks for sides and bottom were nailed and then sealed. Lupe had told them that only a few old artisans on Scorpion Island could make these boats. Rarely were these lakecraft painted or adorned. Each fishing boat, however, had the identical elegant, narrowing prow that curved to a point a meter higher than the water.

She said, “Someday I’d love to own one of these beautiful boats.”

He would dream with her. “You deserve one nicer, more elegant. Safer.”

“No. This is what I like. This is the one. Aren’t the lines beautiful?”

She let go his hand and sat cautiously upon the upswept bow; it accepted her weight without shifting. She passed her other hand fondly along the gunwales of it. Her eyes followed the caress of her hand. Then she turned to face him and said, “Isn’t it amazing how all this is turning out?”

His head was very pleasantly light from the wine. This sudden, new, who they were, Bellacasa, made him feel like he was considering the life of someone else. “It’s going a little faster than I expected. Are we ready to build someone a house?”

She beamed. “How about two houses? I was saving it to tell you. Another agent called me today, asking about our lots. She has someone else who wants to build. So you tell me–are we ready?”

He laughed. Yes, this was what dreams were made of. “How can we stop now? I assume we say yes to all of it.”

She glowed. “That’s what I say too! Lupe will have to hire a lot more men. That thrills me. And it also means I can go back to California and drive down my blue Chevy pickup. It’s my baby, you know. I’ve been thinking about it, missing it. Mexico is what it was born to do.”

He loved her like this. “But this is the ultimate question–aren’t you as happy as you get?”

Perhaps it was an unfortunate question, for Carlotta let slip both the smile and the laugh, and soberly said, “Not quite.” But then she laughed. “You know what I want. Even if we don’t talk about it. Hey, it’s not my fault! You asked the question. Besides, romantic nights bring up these things.”

She saw in his eyes tonight that he would give her almost anything. He said, “No–talk about whatever you want. I love seeing you happy, seeing that in your face. And knowing I helped put it there.”

The princess was again pleased. “Well you did. And I thank you. Yes, you know what else I want. And you know I’ll wait. And I won’t press you. I was just answering your question–which is no, I’m not as happy as I can get. Though this is all quite wonderful, I will admit.”

He pulled her close. He couldn’t quite say it, ask it; but he did say, “You’ll get everything you want, I promise you. I’m almost there.”

So here she was, a year and a half in Mexico, sitting beside Lake Chapala with this man she so loved, on the happiest, most romantic night of her life. And again, his words would just have to do.

3: MAESTRO LUPE

Guadalupe Gonzalez, maestro of the obra, stood on the boundary where the diablo Kraburn’s property joined the dirt road that was Calle Mina del Oro. His arms crossed upon his chest, he watched his maestros and peons move like an army of ants from the mound of wet cement and the gas-powered mixer on the road behind him. They plodded down their uneven slope of trail to the frames that shaped this foundation, so long abuilding that it could not be believed. Each man carried on his shoulder a twenty kilo bucket of fresh cement. Two others stood on a platform beside the foundation to receive each bucket and pour it into the massive forms. A column of men trekked back with their empty buckets the way they’d come, passing the approaching others, who were yet unburdened.

Behind Lupe was a plastic tarp that looked like it covered a car, but which in actuality covered nine tons of powder cement still in bags stacked beside the mixer. Beside those was a man-tall mound of gravel. Beside that was an equally massive mountain of river sand.

Also upon this road that went nowhere, four other peons cut and formed several thicknesses of rebar into long armatures that would reinforce the foundation where the engineer’s plans so specified. The engineer had personally shown them how to build the iron forms that allowed them to bend the rebar into the shape of each armature. More than a hundred lengths of five meter rebar lay beside these four peons. A dozen formed armatures lay beside them ready for use.

In all his twenty-two years of working construction Lupe had never seen such a foundation. The base of it was a meter thick. The far wall of it downslope was six meters tall, so that the principle floor of the house would be level with the road. They had been digging and framing and mixing and pouring and making armatures for weeks. The foundation looked like a military fortress, itself bigger already than most of the houses Lupe had built. It would still be another week before they laid their first brick of wall. The finished house would be two tall floors above the street. Every day when the señor came to look at it Lupe saw the misery in his face.

This unprecedented labor caused other problems for maestro Lupe as well. It was customary for all, maestros and peons alike, to share the labor of digging foundation trenches, mixing and pouring cement to fill them. But in all the houses Lupe had worked this initial labor was a thing of a week, hardly ever more. After that the division of labor was well defined. The maestros set stone and laid brick, plastered the walls, built fireplaces, built cupolas, built scalloped and vaulted ceilings, and laid the tiles for the floors, and in the kitchens and bathrooms. The peons assisted them, performing all the strenuous tasks of preparing cement and mortar, hauling brick and iron, hauling water. As well as that, they also did the tedious jobs of sifting sand and grouting bricks and keeping the jobsite well ordered and clean.

But this foundation and all the mixing and lifting and carrying–there was no end to it. To maestro Lupe it was a measure of the good character of all his maestros that no one complained. They had all worked together many times, many years. Cousins, brothers, nephews, uncles, friends. All from Six Corners. And Lupe knew as well that half the reason no one complained was because it was for the señor. And the señora. They had become a compania. There would be many houses. Continuous work. For many. If this pinche foundation did not bankrupt the señor and shatter his courage.

Lupe’s eyes drifted beyond the foundation, down the long slope of hillside toward the carretera, and even beyond that, to the small, frail and mostly adobe structures of his barrio, which had been there hundreds of years, no one knew how many. And just beyond Six Corners, the resplendent lake, one hundred fifty thousand years situate.

In the heart of Six Corners he spotted the cross upon the iglesia of the Virgin, around the corner from his own adobe house. This recalled to him the preparations sister Magdalena was even at that moment making for the party that afternoon. This thought made him wish to smoke a cigarette, though he had none. He knew he would have to buy a pack, or two, before he was home. The last time Tacho had seen him he had smoked. Tacho would not think it unusual to see his father with a cigarette. But these thoughts began to make Lupe’s stomach churn again, and he paced away toward the houses at the neighborly end of dirty Mina del Oro, where it abutted Calle Rio Nazas, the long cobblestone street connecting them to the carretera downhill.

Then he saw a thing that stressed him as much as thinking of the party: he saw the señora’s old blue Chevy pickup, which the señor usually drove, coming up Rio Nazas, and no more than a car length behind him the new red jeep of Señor Kraburn. That, for Lupe, was the story exacto, the red diablo on the señor’s ass.

His instinct was to call out and warn the men that the diablo was coming; but he knew it would serve no good purpose. So he merely watched him pursuing the señor’s truck up the hill. Already Lupe had begun to withdraw into the sanctuary of his apparent ignorance of the diablo’s language.

The señor parked beside Lupe’s battered twenty-two year old Cadillac of all problems, got out and slowly walked toward him without waiting for the diablo. The señor smiled. Perhaps there was some rare bit of good news. Or more likely he had already prepared his own sanctuary, the smile that could not be broken down. There would no doubt be many questions and directions and dissatisfactions that would be announced by the diablo, and there would be for the señor no hiding from these words. He would answer them all from the sanctuary of that smile that could not be broken down.

The señor stopped beside him and studied the work. He wore as usual his levis and a dark green tee shirt, and the naked huaraches with only the Y-strap over the toes. Curly graying hair over his ears, the señor was a half foot taller than the maestro. As Lupe watched two peons pouring buckets of cement into the foundation frames, he glanced to the señor, who smiled truly, and said to Lupe as he always did, “Buenos dias, maestro.” His Spanish sounded very nearly like their own. Rafael, Lupe’s nephew, half deaf and also impeded in his speech, walked past them carrying two armatures, and the señor spoke his name and greeted him also.

Lupe tried to give the señor courage; he swelled with enthusiasm. “We will finish the fortress this next week, señor, then we can begin the walls. Pues, it will go fast, you’ll see.” Lupe saw Kraburn come out of his car of the true diablo’s own red color, and walk slowly toward them, lighting his nasty cigar as he walked.

The señor said, “When will Figueroa come with the bricks?”

None of these details ever escaped the maestro. Lupe spoke with great confidence. “Pues, señor, he will be here this afternoon, without doubt.”

Without looking Lupe knew that Kraburn had halted behind them, though for a long ominous moment the ghost said nothing. When the words did come they sounded playful and friendly, though Lupe knew they were not, but merely the sound of the assassin who enjoyed his work.

Lupe’s English was a long work in progress. Over years he had accumulated a knowledge of many words, and especially those of construction. He knew no grammar. And odd dialects of English baffled him, as did the slang terms that made no sense until someone like Marcos his nephew explained them. The señor spoke his English slowly and distinctly, so Lupe could understand him most of the time when the señor spoke to other gringos. Though the señor without doubt knew it not. And of course Lupe never spoke English. The pronunciation of this Kraburn, who knew no Spanish, sometimes was clear, though at other times he seemed to slip into his own peculiar American dialect that Lupe could understand none of. But Lupe knew that Kraburn’s first words spoke the usual dissatisfaction. The work was going too slow for him.

This seemed not to bother the señor, not this fiftieth time. He answered him what he usually answered, that they were going as fast as possible, that Kraburn could not expect with so much foundation that they could have progressed any further.

Kraburn said, “Hire more men, you’ve got a deadline.”

This word deadline made Lupe grit his teeth. He would not look at the tall, pushing man. Most gringos loved this word deadline. It was more important to them than anything. In honor to it they were rude, barbarous even. Building the house in Chula Vista the señor and the señora had never been guilty of this. That if nothing else made them unusual. But in the house for the diablo the señor had several times been impatient and had used the word deadline; though Lupe excused him, because he knew it was the diablo pushing him, always pushing him.

The señor told the diablo now that if there were any more men on the job they would be bumping over each other constantly. And that was true. For a long moment this Kraburn said nothing. Lupe glanced at him: this gringo smoking and so well pleased. Lupe looked away, then heard him speak. “Last night I was looking at that first set of plans you gave me–remember that? The ones you based your price on? I was comparing them to the foundation plans the engineer in Guadalajara made for you.” He snickered. Lupe knew he was saying this only because he enjoyed reminding the señor of his great mistake.

The seññor said nothing. And what could he say? Lupe took some of the blame for this–he too should have known. Pues, actually he had suspicioned. But it was very hard to tell sometimes what the angle of a slope was. Lupe had not seen the señor’s plans for the foundation until they’d begun work. And it had been Lupe who had finally said, We must stop, we must bring an engineer from Guadalajara to look at this. And he had come to look, and then the engineer had drawn the plans that Lupe had almost cried over when he saw them.

Several huge pages. One page alone with drawings of all the complicated and expensive armatures that would have to be built for reinforcement. A triple thickness of foundation. Several massive pads of concrete and rebar anchored deep in the earth to support such a tall foundation at its critical corners. And no limestone to be added to the concrete. None. The señor had to pay the engineer to come to the job site several times just to help Lupe read these plans, so complex they were.

Lupe heard the diablo walking away. The señor watched him too, as the diablo went to scrutinize the peons making armatures. The señor walked that way himself. Lupe followed them. The diablo wore a bright flowery shirt. He wore khaki shorts and cleated rubber walking shoes. Long dark hair combed forward to obscure the lack of hair near his forehead. The man grinned; evidently all this strain and stress of contractor and foreman and workmen pleased him much.

Kraburn said to the señor, “No wonder you’re so slow. All those men working together there–see them laughing and talking?–that’s wasted time. I learned that a long time ago, training my assault team. Keep them isolated. You get a lot more accomplished.” The señor made him no response, as if what he’d said mattered nothing, which it didn’t. Yes, Carlos and Porfirio were talking and laughing–why not? Then the diablo went on. “Maybe you forgot–you promised me I’d be living here by Christmas, and I’m holding you to that. And I mean it.”

This was how he did it, little by little, pushing the señor to the brink. Dead-lines. Lupe saw the señor shake his head, as if to make that annoyance go away. He said, “Hey–we had two months more work than we’d planned–all to your benefit, and at no extra cost to you. You know we can’t still be done by Christmas.”

The diablo seemed not to hear him. He pointed his cigar at Carlos. “See how slow he works? Better supervision’s the answer here. Get him moving. Get them all moving. They’re all slow as hell. Take my advice and you’ll make up your two months, save a little money and we’ll both be happy. The truth is, I could save you a lot of money here, if you had the sense to listen to me.”

Lupe was happy the señor was not responding to this, for Lupe had come to see that Kraburn liked to be contradicted and argued with. He always had more to say. Such cajones. He must know they all hated him; yet he loved to come here and tell them what to do and laugh at them. And always–hurry, hurry–never forget the Dead-Line. Marcos had only just told him that this evil word described a procession of those who had died. The diablo should think about this.

4: WELCOME HOME PARTY

Three months Lupe had longed for and dreaded this Saturday afternoon in July. He had returned from the jobsite to the barrio with all the men who would fit in his 1979 Cadillac of all problems, and he had parked in front of his house on Calle Obregon. But then, instead of going into his house where so much awaited him, Lupe walked the half block to Six Corners and turned right to walk the further block to the iglesia of the Virgin of Guadalupe, his name saint.

He passed old Arturo the butcher standing in the doorway behind his counter, waving away flies from the cuts of raw beef heaped on the counter. Arturo called to him and winked, for he also knew this was Lupe’s big day. Antonia saw him too as she cut limes at the card table set up outside her doorway, for the customers who bought her crisp delectables every day: Chicharrones y limones ooolala, she sometimes sang. She waved, then thought to ask if Tacho had yet arrived. Lupe told her yes, yes, yesterday, staying of course with Tia Costanza Romero. Antonia had nursed Tacho when he had been so severely ill with the grippa that winter, many, many years ago. She had been Marlena’s closest friend, and she like all the others had advised Marlena to leave him eleven years ago. And look at her now, waving, smiling. Antonia had forgiven him long ago.

Roderigo, half drunk and unsteady in the street, saw him too and stumbled toward him with great urgency. “Lupe, Lupe,” he said, “you must help me. My idiot son I think is going out nights with the bad ones again, I’m afraid he’s stealing. Help me talk to him.”

Today was not the time for it. “Come to my house tomorrow, Roderigo. No, no, come Monday, after my work. Then we’ll talk about it. Today I have important business of my own.”

Roderigo came close, put a hand on Lupe’s shoulder, partly for friendship, partly to steady himself. He breathed his contaminated breath into Lupe’s face as he said, “Oh I know, maestro–Tacho has come home. I know, yes. Then I’ll come Monday. And I’ll pray that until then my son is not put in jail.”

Lupe hurried on, only greeting and waving to those he could not avoid, and to those only briefly. At the little store in the doorway of Señora Santos, whose son Guillermo worked as a peon at the Kraburn fortress, he bought two packs of Toro Bravo cigarettes; but then had to suffer through the nosey Señora Santos’ wishing him well seeing Tacho again that afternoon. Yes, it seemed that everyone knew everything.

He stopped at the open doors of the iglesia, the bright daylight illuminating everything inside, where only four or five alone there prayed. The great painting of the Virgin hung upon the wall behind the altar, perpetually blessing all the humble citizens of the barrio. Lupe hesitated, wanting not to encounter Padre Morelia, who would be friendly but who might also want to make comments about Lupe’s very rare visits to the iglesia. Not seeing the padre, just as he had expected not to see him this time of day, Lupe entered. He took a breath to relax himself, to breathe in the holy air, that it might stabilize him, invigorate him, make him worthy.

He walked silently to the nearest row of seats, kneeled and crossed himself, then sat. And waited. With eyes closed. And eyes opened. He stared at the compassionate Virgin, who loved all sinners. Even great sinners. He waited for momentous words to arise in him, that he might express and plead his case eloquently. He had a great desire to express and plead. He waited. But no great words came to him. Until he began to feel himself unworthy even of a good man’s prayer.

No, this was not making him feel better. He crossed himself again. He uttered silently a simple prayer that he be forgiven those old crimes against his family, that he be no longer tormented at night by the bad dreams of recent weeks, and that Tacho might forgive him and accept him as a father again. That would have to be prayer enough. He crossed himself. He stood and stepped into the aisle where he kneeled and crossed himself again. Then he walked out and away from the iglesia, feeling no better or worse. Lupe reflected that it must be as the padre had since long ago warned the congregation–the Virgin cannot be used to satisfy personal desires.

Yet when he turned the latch of his own front gate and stepped inside, when he heard the musica and the loud laughing voices, he knew Gloria, who always came to him, and Marcos, who’d been through all of it with him, and sister Magdalena–they would be there for him. As would be his fellow maestros, several of whom were Romeros, but who had stood by him in spite of that. And hopefully the señor and the señora would be there. That might be enough.

Lupe stopped, stealthy as an intruder, and looked into the yard. He saw Old Marcos pass by; he saw Gloria’s friend Isabel sitting primly in a chair listening to someone Lupe could not see. The musica was from a radio in the main house, the obnoxious rock and roll that meant the young ones were inside controlling the musica, when he himself had planned for the mariachis. With the musica was probably where Tacho would be, with all the cousins. Lupe realized that the yard then might be for the moment a safe-zone where he could settle a moment with his allies, have a last cigarette, and then...then face whatever would happen.

He peeked his head around the corner. No señor and señora. Que lástima. But Marcos was there, poking in the adobe oven at the birria. His father, Old Marcos beside him, was telling his son that the birria had been in there more than enough time. Two card tables stood near them, with paper plates and plastic cups and double liters of Fanta and Coke. A bowl of guacamole, another of the fried frijoles. Old Jesus sat across the yard in one of a dozen white plastic chairs that had been set out. Jesus saw Lupe and grinned and lifted a plastic cup that Lupe knew would be half tequila, half agua mineral, toasting him. Five others who had lived on his block of Obregon all their lives now occupied five other white chairs. As each one saw Lupe advance a few steps further into the yard, they called out to him.

Gloria, who had returned to sit beside Isabel, heard this and looked at him and smiled. “Oh Lupe, you’re late for your own party. Tacho’s inside.”

Marcos also looked at him, and grinned to see the terror in his face. He called out. “Have a tequila, hombre. Or a little mota, that’s what you need.” None of them could see what bad jokes these were. He walked to Gloria, who hugged him well, just what he needed, and she spoke intimately to him. “He’s such a handsome boy, Lupe.” He stood free of her, tried to smile what good news that was as he opened the new pack of Toros and lit one nervously with a lighter Isabel handed him. Gloria leaned close again and said, “Let me take you in the house. It will be worse the longer you wait. He’s happy to be here, he’ll be happy to see you”

He let her lead him forward as he quickly practiced his smile of recognition, but he knew it was a bad smile and only made him feel even worse. Passing through the door he heard young voices. He looked with rapidly rising alarm at the three seated on the sofa–no, not these–he knew these faces. He continued on behind Gloria, smoking, smoking, toward the kitchen, toward the loudest voices, seeing over Gloria’s shoulder Antonio, Porfirio, David, Rafael–and then the face that didn’t belong with these, indeed a handsome boy, the handsomest of all–such a smile!–making them all laugh at his joke. Lupe stopped walking, but couldn’t stop staring. Eventually he saw the ash of his cigarette ready to fall and he looked about him for an ashtray, even as he realized how foolish in everything he seemed now. Gloria mercifully took the cigarette from his fingers and nudged him forward. The young ones stopped talking.

Tacho stood several inches taller than his father, in fine clothes that could not be found in the village stores. His hair he’d combed straight back, and the dark eyes sparkled. The face was just as Lupe remembered it. Yet Tacho was a man. With all the memories of the boy.

Lupe became rigid in the unbearable silence that ensued. It seemed he could not move or speak. Someone said something. Someone laughed. Then as if he were watching from faraway he was aware that Tacho and he somehow stood together, embraced awkwardly, said something to each other, and then stepped apart, both continuing to look at the other, both seeing a great mystery. Then each one laughed self-consciously the same moment, and then each looked away from the other.

Lupe saw them all in his kitchen. The five young men all leaned against the sink counter, three of them drinking Corona cervezas. Seated at the kitchen table was Maria Perez, Porfirio’s merry wife. There was the gas stove. The refrigerator. Gloria standing beside him. All as it always was. And yet there was Tacho too.

Tacho said how he was, how he liked the village now. Lupe said how he was, how things were going. Yet after these first words were spoken Lupe remembered nothing they had said, nor could he imagine any new words to speak.