1: The Escape

One September night in the middle years of his life he awoke suddenly, frightened by a dream. On a vast, dark sea he’d drifted, naked and alone on a flimsy raft, beneath an immense canopy of stars he’d never seen. Not a sound he’d heard; nor could there be any shore to this desolate ocean.

Awakened in a cold sweat, he lay in bed beside her, staring into the bedroom’s warmer darkness, waiting for the stark, sinister images to fade away. But they did not; and soon he saw that it had been not a dream, but his own weary life come to plead with him.

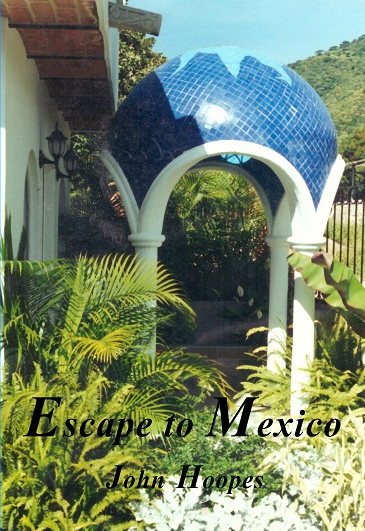

Before the Sun rose, he conceived that his only escape must be a blind leap into the void. Within a week he sold the business and took the money and flew away, his purpose hidden, to a fishing village in Jalisco, Mexico, on the shores of Lake Chapala. He bought a vacant lot in a residential neighborhood; simultaneously he met an honest maestro from the village, who built houses. Ajijic was faraway and picturesque; he might even write another book there.

He returned home a week later to Mill Valley, California, to Elena’s cottage in Blithedale Canyon. He told her everything he’d done in Mexico. She was dismayed and depressed.

Days before he’d returned from Mexico, he had prepared his apologies and persuasions, but as he stood before Elena, who was six feet, and taller than him by an inch and a half, she was formidable; and even moreso because she also had an indisputable grievance.

She shook her long auburn hair and would not give him anything. “This is hard, that you didn’t include me in this. It’s just shows me that your life can suddenly go a new direction, and I’m left standing here. You know I can’t accept that.”

A year ago he had gradually moved in his books and clothes, and finally given up his own apartment in Sausalito. He was surprised to hear her speak of abandoning. “Oh no! I want you to go with me. Whenever I’ve thought of this, it was us, doing it together.”

This somewhat appeased her; she surrendered to him half her resistance. Yet she was still angry. “But you should have told me. Something. Hell, it’s your business and your money, but we are at least sharing lives. Or so you say we are. But if you don’t see it that way, how can I trust you? Lake Chapala is a long ways away. And I can imagine you just running off again, after God only knows what, leaving me stranded there.”

He tried to smile her doubts away, but she didn’t accept that. He was a vagabond, and she knew he would always be. Even so, he was full of an energy she admired that moment, even while he complained: “I’m sick of all the crap I’ve been doing all these years, to keep from having an eight to five job. The crap that made me good money was too dangerous, and the crap that was respectable didn’t make any money. If I can’t see some way out of this, I think it would be the end for me.”

Still, it astonished her. “But you don’t know anything about building a house, Jay. You didn’t even do that much carpentry with Ben.”

Even in the late California autumn Jay wore tee shirts and levis and Y-thong sandals. His hair was thoroughly gray and grew abundantly curly over his ears. He said, “There is no carpentry in Mexico. It’s all bricks and cement and iron rebar and stones and tile. They don’t even use power tools. The only thing plugged in that I saw was a ghetto blaster. Look–we’ll watch them build our house. We’ll live in it. Then maybe we’ll sell it. And then who knows what?”

It was a pretty picture. But she had always lived in beautiful Marin County, a woman of the woods and hills and creeks, and this was much to leave. She had cats. And deer and raccoons. She pretended to weigh his proposal.

He gave her little time. “Elena, you have nothing here either. Twenty-two years you’ve lived in this little place, next door to old, needy, tyrannical Isabel the invalid. It’s a nice cozy little living, but gee, my dear–twenty-two years?”

She knew it. Though that argument was irrelevant, since she loved him and she would go with him no matter. Even so, she continued staring at him intently, no doubt trying to uncover something more in that face and those eyes, something he himself couldn’t help her with.

Although his eyes looked deeply into her eyes too, and he could see everything hidden in her heart. So he spoke the clearest truth he could perceive in the muddy waters inside him. “I want you to go with me. I need you. Please trust me. You know how much I care about you.”

“Alright,” she said, finally dropping her eyes away from him. “I guess that’ll have to do. But I will insist on one thing. If you’re taking me to Mexico, I want to be there for All Souls’ Day. I want to be there for one of those celebrations in the cemetery. I’ve shown you pictures.”

“You have. And that’s November first, isn’t it? We’ll have to hurry.”

And so they came down out of the north on the first day of November, the days darkening, six years till millenium’s end, hoping to cross the border into Mexico on All Soul’s Day, hoping to find this celebration of the dead and with it to warm their hearts and to bring the life back into them, knowing so well that this disease of California melancholia was consuming them.

They drove south toward their new destiny deep in Mexico, but he could feel the never-sleeping ghosts of his past laughing at him as he tried to escape: decades of narcotic abuse, the abandoned marriage and its memory of lies and heartaches that he would never be rid of, and yes, the great ghost of all the dark alleyways of illicit commerce he had haunted: yet drive on they did, without looking back, though he knew the odds were against him, the old fool, fleeing too late his mistakes and his doom.

But Elena was at his side, driving the heavily freighted van without fear, even knowing the doubts and dreads that haunted him and which seemed never more distant no matter how many miles they raced ahead beneath the gray smothering sky. They’d brought with them twelve or fifteen boxes, a slim inventory of their lives, and the three unsuspecting cats who were her children and family, huddled unhappily in a cage in the back of the van where she could watch them in the rearview mirror.

Highway 5 was their onramp to mexico antiguo, a straight launchingpad 400 miles through the long lonely valley of California and the especial barrens of those southern deserts where 75 miles an hour seemed slow moving. They accelerated through the mountains beyond Grapevine, passing everything, and they flew down toward San Fernando in twilight, seeing even then the ugly brown stain of sky ahead that signified the fallen city of angels. He wanted to go straight to the border, cross that night, but the maze of LA ahead was too much to consider and he begged Elena to swing wide on the Pasadena freeway and carry them partially north and away from the misery of that fabled and grim metropolis that reminded him too much of the battered spirit within him he was so desperate to make whole again. It was black night on the faraway outskirts before the commuters had them trapped in their slowdown of tailights and headlights, but by then he didn’t care because they were nearing Riverside and Mojave, and LA was behind them, and even if they didn’t cross the frontera at Nogales, Arizona, till the next day, the plague of the city of angels was passed and the day of the dead in Mexico was still to be found.

Waking in Indio the next morning he was restless and irritable, sensing something unimaginable and invisible tracking him. They raced again across bleak deserts, today Arizona, bypassing Phoenix and then south toward Tucson, stopping only because they needed the gas and Elena a meal. Aloof from his restlessness, she sat placidly in her counterseat, waiting for her order. Her wide-brimmed stylish hat rested so elegantly on her head, so gorgeously out of place in that high desert burger joint.

He’d been warned against night driving in Mexico, and for two days he’d hurried them on toward some unknown sanctuary beyond the border where they’d be free to rest by sundown, a border passed that might at last give him the first sense that he was free and away, and where Elena would be able to have her longed for moment in Mexico, where they truly honor their dead in joy and candlelight and all their so glorious color, a shrine where she could honor the dead three who were always in her heart, Dead Larry, Dead John, and his own dear Dead Ben, who had all within these last four years made them so deeply grieve.

At the last gringo grocerystore in Nogales they did indeed get the necessary cat supplies and plenty of water and a toothbrush for him and meat for sandwiches, but in the van as they came in sight of the border towers she realized with a moan that somehow the special candles had not made it out of the grocery cart into the bags, and the guilt was all over him, even though he couldn’t remember forgetting them, but knowing he had not seen her through on this, for her, most essential item of this day of their journey, for there they were at last to Mexico, though barely, and barely ahead of the fall of night, and yes, they had made it, barely, on All Souls’ Day. But beggars to the fiesta with no candles to honor their beloved dead.

They crossed the border as night fell with hardly a wave from the Mexican customs. Now he drove ahead with great caution, watching the tall weeds at the roadside for cattle and burros and dogs, calculating that Hermosillo was probably three hours ahead if he had the energy to push it that far. But soon the road narrowed, and they began to see battered and half-eaten carcasses of coyote at the road’s edge, and signs that bid them beware of stray cattle. He strained to see into the darkness beyond headlights, so that by the time they came into Santa Ana, a mere 70 miles from the border, Elena and he were both tense and tired and he gratefully accepted her suggestion they stop there at that desolate waystation.

The clerk at Motel Elba would accept the cats, so he looked ten seconds into the room, it seemed pleasant enough, he paid the clerk. They brought in the cats one at a time, then a few bags and boxes, and Elena looked carefully into the bathroom, the dresser drawers, under the bed and into the corners, and said with deflated energy, “It’s a dump.” Which of course by then he was realizing too as he looked around: peeling wallpaint, broken drawer handles, old stained bedding, two pathetic little lightbulbs keeping it all in merciful obscurity. But the cats were safe, and he didn’t have to drive anymore that night, and he could see that Elena was already overcoming the squalor, going through boxes and removing her little treasures from their newspaperwraps and arranging them on the TV, on the lampshade, over the Aztec calendar, wherever there was space. And finally creating a shrine on the dresser with three of her old nearly consumed votive candles set in front of the bronze of three angels that represented Larry and John and Ben, and she placed paper flowers out of her box around them and lit the sad votives and that was it--not remotely the gay cemetery celebration she had been planning these last few weeks, but they had made it to Mexico, in time, and they were indeed saying their prayers to the dead with the rest of the pagans.

Jay and Elena had lived their third year together in Olema in west Marin county on that beautiful coast on the most wonderful fairytale piece of land either one had ever known. They moved in right after Ben died.

They were both cripples when they met, he only didn’t know it. She had just lost Larry, young and handsome, her more than brother who had been her sidekick sixteen years, in business, in sorrow, in play, in all of it, though not her lover but John’s. Larry died of AIDS despite all her bedside nursing and pleas to the gods; despite her long marriage and many lovers, he was the true love of her life. That was her crippling.

Jay’s was the result of a shipwreck of love and lies that had poisoned his wife and him to each other, made poignant and forever renewable grief with the daily comings and goings they still had with each other because of the two children together they shared and both so passionately loved, and who could not but remind them of the great joy they’d all had together but which they two, in their ignorance and separate suffering, did not fully comprehend and honor, and therefore let it go. So his own crippling. He still loved them all three.

He met Elena nearly a year after Larry’s death. She was beginning to withdraw from her mourning, and to grapple with the apparent emptiness of her life. But the shadow of death still hung over it, for Larry’s mate John, her other dearest and oldtime friend, also had AIDS, though he was full of life as ever, with all the signs of good health otherwise. So when she and Jay met in Sausalito that night they were a good match, even if he couldn’t see it, because he was already a few months struggling with Ben’s leukemia diagnosis, refusing to believe anything could bring down that mighty soul, the masculine, sans sex, love of his life.

Jay was still lost in the blind alley of his old lost love with Carolyn, and he couldn’t admit to himself and certainly not to Elena that he could be in love again, so he could only come to her silent and in need, and she took him in under his selfish conditions and held him and loved him and put up with him and didn’t ask for anything more. And they shared their sorrow about Larry and John and Ben.

Fate pressed their common suffering into their eyelids, Elena’s and Jay’s, the day he took Ben to the hospital for a last desperate new chemotherapy treatment. He was reduced to bone and slack skin, the deathly purple blotches on his body, time run out, and there was this one last hope of treatment, or death. That same day John called Elena to say that a minor affliction had sent him to the hospital also, but he wouldn’t miss the big party that weekend they had been organizing for a famous rich client in the Napa Valley for weeks, and she was only mildly worried.

But Fate is an unruly and unpredictable bitch, and Ben’s chemotherapy within a week had him looking like a new man, alive and laughing and planning the rest of his life. John’s affliction, to their horror, turned to meningitis, which could not be treated without destroying his already fragile AIDS-ravaged immune system, and in a week John withdrew into coma and died. Her second crippling.

When Ben’s chemotherapy was doing so well six months later and we were all so optimistic about his recovery, Penelope, his mate of eight years, bought that magnificent five acres in Olema for the two of them to share, a secluded garden of eden hideaway where Ben could heal and come back to himself and to them all. Because Penelope’s daughter still had a year of school and they couldn’t move in for that time, they wanted someone to live there who could appreciate the place and would take care of it. So Ben took Jay and Elena out there one spring afternoon before the sale was final, and those three sat in a meadow on that sacred ground and he looked with passion into Jay’s eyes and said, “Well...do you love it?”

Well, yes he did, but he was not passionate enough in his response, and Ben asked him again, forcefully, “No--do you love it?” Jay had only been there fifteen minutes, and he would have said he didn’t have Ben’s depth of soul that could see in a few minutes just what a paradise that place was, but he understood Ben’s intensity, so he forced it out of himself to match him, a little lie, and said, “Yes! I love it!” But very soon, yes, very soon, he loved it like Ben did, and Jay thought of him everyday in the afteryear that he lived in that wonderful place.

Because, Fate being the unruly bitch, Ben’s leukemia bolted suddenly to crisis and he died before the property closed escrow. When Jay and Elena moved in Jay brought the four polished stones from beside Ben’s front door Ben had always used as a trailmarker, and he set them to mark the garden trail in Olema. He dug up a favorite rose bush, Sterling, from Ben’s yard and transplanted it beside the front gate in Olema. And in that year he planted all the gardens and the orchard and the fencelines there with the yellow poppies Ben had loved so much. And that marked Jay’s second crippling.

All Soul’s Day that year in Olema was Jay’s first experience of that holiday. He had been working all day and had come home after dark. Elena met him at the door with a profound smile and led him silently by the hand out to the back deck. From which was visible in moonlit silhouette only rolling hills and primeval forests in all directions, but where he saw in amazement their eating table on the back deck covered with dozens, dozens of flaming candles--tall ones in elegant holders, simple ceramic holders, fat ones in hurricanes, slim candles in tiny cups, and so many votives in all their assorted holders--there must have been fifty or more candleflames in all fluttering there on the table in the silent holy night under that crisp black sky and the jeweled stars that so perfectly answered the candleflames. And there were three champagne glasses beside a chilled bottle of her favorite Chandon, and three plates of chocolate cake slices beside them. And perched on the deck rail beside the table were her three pale ceramic angels, each on its own pedestal, each with its own exquisite inscrutable stare into eternity, and she had tied thin black ribbon around each of their necks into an elegant bowtie for the celebration. Jay was stunned into sacred silence, for neither did words become uttered even in his mind as he stood there and let the majesty of that magnificent moment fill him for all time.

And they sat together on the deck in the continuing gaudy silence of that night and poured the champagne into each of the three glasses, and they toasted their three dead darlings, and ate their cake and held hands as the candleflames wavered and danced and the stars twinkled back overhead.

The grim Motel Elba in Santa Ana was only a waystation so Jay was not unduly saddened by the pathos of their room. But the signs he saw in Elena that his rosy picture of their new life in Mexico was for the first time arousing doubts did make him nervous, and he would like to have said something to mollify her, but his jokes and attempts to distract her did not make her smile. The rumbling of trucks down the highway kept her from sleeping, as well no doubt the thoughts that rumbled through her head. Before bed, the enchiladas next door were so bad she’d refused to eat them, and he knew she was hungry but she wouldn’t talk about it.

Their ultimate destination was the perennially springtime shores of Lake Chapala and the happy little village there of Ajijic a thousand miles south of the border. Jay could look again at the pictures in his memory of Ajijic that he had been cherishing for the six weeks since he’d gone there and bought the property, violating a promise to her that he would only look, and he knew everything was going to be OK once they got there, and that she would forget this dump and she’d be able to laugh at the jokes that tonight were only making tears in her heart. He was shifting nervously in bed himself now because he was uncertain suddenly if he was remembering all that correctly and even more, that if he were she would see the same things there that he had seen, and that she would feel the way he did.

But Elena was formidable, and when he awoke an hour after dawn, having slept well all things considered, she had already been up long enough to have repacked the shrine into boxes, repacked her treasures so as to once again reveal the even greater ugliness of this room in the unmerciful morning light, repacked their clothes and even the cats, and she was dressed and ready for the road, and he knew as he dressed in silence after the quickest of showers that she wasn’t going to suggest any stops for breakfast in this wretched little town before they hurried out of there.

Yet in minutes they were in open country, the Sun was bright, the sky blue, the scenery was all saguaro cactus and bizarrely shaped mountains and quaint little hovels near the roadside with exotic women standing timelessly in the doorways and burros led down dirt trails by old men in dusty white pants and shirts, and all the strange Mexican roadisgns, and they were smiling and laughing at each little thing.

And the day went on like that, two lanes each way, separated from the oncoming traffic, easy as driving the US. Late morning they were in Hermosillo and they stopped for a meal after carefully driving up and down what looked like the main street until they found a little Mexicany hotel-restaurant that was serving a few well-dressed locals, which seemed a good sign. She ordered eggs and beans and hashbrowns, and he had a simple enchilada plate which was good enough, as was her breakfast, and they did indeed walk away from it feeling filled and without any indications that they would be suffering later.

The rest of the day he pushed it as near to top speed as he dared, hoping to make Mazatlan by dark, for that city he knew and trusted, even gaudy with turistas and obnoxious as it was, he knew they would find a good rest there and a good meal, and perhaps even have time for a stroll on the malecon. The toll roads continued, gouging unmercifully, but he knew it could be worse, they could be driving in terror the two-laners of yesteryear with the eighteen wheel diesels that he remembered roaring down on him and passing with impunity whenever the hell they wanted to, and you either got out of the way or died.

But even with this modern day Mexican highway he was still having to slow down every ten or fifteen miles when they passed through all the dismal little towns along the way, and by nightfall they were still too far from Mazatlan, so they agreed to stop at Culiacan, and that would leave them 500 miles or so the next day to Ajijic.

With only minimum difficulty they found a hotel and by then in the maze of city streets and the deep dark they didn’t hesitate when they were charged a hundred US, for here they didn’t care about the cats either. The grounds were semi-elegant, and the lobby and the restaurant were the same, and no doubt the rooms too once were. But tonight the hot water was only warm, the air in the room was hot, the window screen was falling off and the air-conditioner after a buildup of a half hour did cool things though it sounded through the night like an old cropduster. But again the cats were happy, and they could rest, and the end of their journey was only 500 miles away, which they reckoned would be easy the next day.

And it started that way, a state of the art freeway welcoming them toward Mazatlan, straight and fast and even landscaped along the divide and they sailed down the coast, little glimpses of the Pacific from time to time, and then a last fifteen dollar toll as they got off the freeway into Mazatlan and they were there before noon. They wandered like the other tourists there along the hotel strip, changed more dollars into pesos, filled up on gas, made phone calls, and wasted an hour and a half there before starting off again.

But suddenly it was like they had lost a century: the road was not just one lane each way, it was bumpy and potholed and corrugated, and even though he kept thinking any minute they were going to come upon a toll taker, whom now he was willing to give more money for a good road then ever he had yet given, the bad road continued on and on, and they repeatedly were slowing for 30 mile an hour traffic, usually several cars and a truck or two deep, or fifteen deep, passing was very difficult or dangerous, but that was the road, and after four and a half hours of that miserable drive they crossed the 180 miles into Tepic, and they were both tired and hoping that the last 160 miles into Guadalajara would not be like that.

Unfortunately, it was not. It was still one lane each way, but it was now mountainous inclines and declines, continually and perilously curvy, and in these stretches the trucks which were twice as many as before and could not go even 30, but only 15 and 20, and the traffic piled up twenty and more deep behind these slow moving beasts, and he had never seen nor participated in more dangerous passings.

Exhausted, they crept into Guadalajara after ten that night, traffic in that metropolis fast and busy, and by some miracle without map or guide they found their way around half the perimeter and to the sign that pointed them to Chapala, and he was happier than he had been since they’d left California, for he knew the rest of it was big freeway and straight to the lake and from there he knew the road right to their Ajijic doorstep

2: The Village

They slept those first nights in their fishing village with the abandon of newborns. They awakened with the Sun well up, sounds lingering in their memories that may have been of the lake and the shore, or may have been of their dreams, or perhaps of another life.

They sat on their terrace on wicker equipale chairs at a round equipale table facing the lake and they ate sweetrolls and drank coffee and hardly spoke to each other for watching the white egrets standing in the green lirio along the shore hunting and the dusky pelicans gliding low just beyond them. Two fishermen in a handmade wooden boat with peaked bow drifted across their view, pulling in net. Elena sighed. Jay smiled at her.

One morning they watched a boy follow three black and white cows along the shore until all stopped in a grassy field perhaps fifty meters from their terrace, and the boy tied the rope of the biggest cow to a stake in the sand and then regarded them with hands on his hips as they chomped the grass. He picked up a stick and put it to his mouth and he played it like a trumpet. Jay and Elena could hear each note of his peppy music. He marched toward the lake, then spun and marched back trumpeting toward the cows. When he stopped playing he looked toward Jay and Elena. She waved. He waved his stick, looked once to the cows, then ran at their terrace grinning.

His white tee shirt was dirty and too large for him, old denim pants hanging loose on his bony hips, toes visible through split seams of his shoes.

Elena asked him in Spanish, “How are you called?”

“Favian.” He stressed the last syllable; he corrected them when they misspoke. Those were his father’s cows. His family lived three streets away. Five brothers, four sisters, uncle and aunt and grandfather. He was not in school today; there was the truant’s sly grin. His ears flared, making his face appear wider than it was. His chin was pointed, his teeth irregular and unclean. His was a simple intelligence, his smile trusted the world. Moment to moment he stepped closer to the glass door open to the living room. He was looking at everything inside, turning back to them only to answer another question.

Charmed, Elena rose and said, “Do you want to go inside, Favian?” Yes, yes he did. Jay rose too and went with them. The boy laid his hand upon the cool smoothness of the sofa arm and stared at the pattern orange and chocolate Aztec stripes and let his hand slide slowly along those bright colors, and then looked up at them and grinned again.

“Do you bring your cows here everyday?” Elena asked him. He said yes he did, even as he turned toward the dark television screen set upon a wooden base just big enough for it. He walked to it and leaned down and saw his face from a darkness looking back at him strangely distorted and he looked up at Elena and his eyes grew wide showing her his delight. But before she could reach to turn the set on he had turned away, his eyes gliding from picture to picture on the walls, all pastels of clean, colorful, rustic Mexican men and women and children doing their simple tasks—nothing exotic or truthful for him there.

“How old are you, Favian?” Elena asked. He arranged his fingers and showed her nine, saying, “Nueve,” smiling and nodding his certainty of that.

Then again his eyes drew away from them and he wandered toward the bedroom but as if he were expecting them to stop him. At the doorway he glanced back only a second, saw their smiles, smiled himself, and walked further. He went to Jay’s computer on a desk near the bed. Jay followed, turned on the machine, and pointed to the blinking cursor. Jay typed out My Name Is Favian in the boy’s language. Jay asked him if he could read that. He could not. Jay pronounced the words, amazement bloomed in the boy’s face. “These letters are your name,” he told him. “F-A-V-I-A-N.” Then Jay typed the six letters again slowly, the boy intent to know the mystery. “Now you do it. First this one.” The boy pressed them one by one as Jay showed him the keys. Jay pressed Print and Favian stepped back startled as the printer began its work. The paper with the boy’s name slid gradually toward them onto its tray. Jay handed it to him.

“This is your name--Favian. You made it on this machine. You can keep it. You can tell your mother and father that you wrote this.” The boy stared at Jay, then at Elena, astonishment fixed on his face.

“Un refresco?” asked Elena, breaking the spell. Enthusiastically yes. All three went to the kitchen, and when Elena opened the refrigerator door Favian stepped within the door’ space and into the cool that billowed out and over him. He laid his fingers on the cold metal grills that were the shelves, his wide eyes saw everything there thing by thing, mayonnaise jar, a cooked chicken under a clear plastic cover, packaged bologna, carton of milk, lettuce in a plastic wrap, a cylinder of whipped cream, incomprehensible. Elena took a Coke and handed it to him. He stepped back to take it from her, not realizing she was also shutting the door until he turned back and the cold was gone and the rest of those things shut again behind the closed door.

He opened his can and drank one big gulp and then wandered toward the rear service patio where a cement clothes scrub was built into a wall beneath one spigot and two rope lines above it strung taut to dry clothes, and a tall plastic garbage can in the corner. Beside it a large transparent plastic bag filled with empty beer and refresco cans. He stood before it staring, then finally pointed at it as he turned to Elena saying “Que es?”

“They’re old cans,” she said. “Left by the people who lived here before us.”

“What will happen to them?” he asked her.

She thought a moment. “We’ll throw them away.” Then she saw it. “Do you want them?”

He brightened. “Oh si.”

And she also brightened at that. “Then they’re yours. But so much to carry for a small boy.”

He believed not. He went to it and hoisted it upon his shoulder, staggered a step, yes; but then turned and grinned at them as he went past them re-entering the kitchen, passed into the living room and through the open slider, but stopped on the terrace, shifted the weight, and then turned to them his happy grin and said, “Gracias;” turned again and swayed with his load of cans down the slope of yard toward the rough open field where his cows still munched wildgrass. But once there he turned to the direction he’d come from, and went that way meandering and sometimes again staggering, suddenly having to doublestep for balance, or he had to stop and drop the bag, take a few good breaths, and then hoist it again and go on. Till he disappeared into the trees down the beach.

The Villas Ajijic were eight bungalows built twelve years prior and arranged along both sides of a central garden path. Two of the units faced the lake, one of these was Jay and Elena’s. The office was at the opposite end of the complex, a counter and desk for the manager, a room open to it with a television and sofa and built-in shelves containing thirty or forty used books of indiscriminate category, and a round waisthigh wooden table kept bare for the use of guests or visitors.

Jay entered the office and stood a moment at the counter, saw no one, and finally said, “Hola” to whomever might hear. Lupita appeared from a room behind the counter, tucked a loose strand of hair behind her ear when she saw him, smiled con gusto, and said in good English, “Señor Jay, good morning. How can I help you?”

Now facing the cheerful innocence of this 35-year-old single mother, he tried to dampen his irritability. “Lupita, the phone still isn’t working. You told us when we moved in we could make calls from our room. And get calls. That’s very important to me.”

She flushed. “Well, yes, I did Mister Jay, but the phone company does not do what they promise me. They said the phones would be repaired today. But they are not.”

He knew by now this may or may not be true. “Maybe I should call the phone company, Lupita. Maybe that would help.”

Her smile became another kind of smile. “No, I don’t think so. It is because they have so much work to do. And because they say they can do something when they cannot. Mexico senor.”

He looked away, shifted his weight from one foot to the other and then back again. Looked again at her, saw the weak helpless smile. He thought he showed nothing of his irritation mounting when he said, “I really need to be able to use the phone, Lupita.”

She tried once more to assure him, even as the cheerfulness in her face and her voice were both dissolving. “I know, Mister Jay, I know. And there will be a phone. I can call Señora Coronado, she is the owner, she perhaps can make something happen.”

Her struggle with this was suddenly apparent to him. And the useless pressure he applied. He paused, then presented her a fresh smile, like the one she’d evoked in him the first evening they’d met. “Lupita, where did you learn to speak English? In school?”

The girl in her face reappeared with a blush. “Oh Mister Jay, I don’t speak English well. I did not go to school. I learned from television. I watched movies with subtitles. And then I watched the same movie again without looking at the subtitles. Sometimes I watched it many times.”

Now he too was relaxing again, enjoying her. She was medium height, pudgy, black short hair pinned back, the sparkle returned to her eyes. He said, “That’s amazing. No, you do speak it well. Better than I speak Spanish. And I studied in school for years. Yes, the truth. But I have not had...the practica.”

“Yes, that is it, the practica. I talked much at first with the actors in the movies, but then my friend who spoke good English said I talked like a movie star, very dramatic, very sentimental. So I practiced with her. But I didn’t know you could speak Spanish, I haven’t heard you speak one word.”

“Not with you, your English is too good.”

“I teach English two nights in the week to young people who come here for lessons.”

“Oh, so you have another job.”

“No no, it is not a job, I only help them. They could not pay.” She studied him a moment, then said, “Perhaps you could come visit my students one evening. It would be good for them, they could ask you questions. Many things I do not know.”

And now she’d slowed him further, he smiled. “What evenings?”

“Tuesday. And Thursday.”

“Maybe I can. We’ll talk again. Now I’m going to the Larga Distancia and make my phone calls.”

She blushed again, her eyes fell away from him. But then she looked up, determined, and said, “Mister Jay, the truth is that Señora Coronado has not paid the phone bill. And it is very much, I cannot pay it. She gives me money to pay the accounts, but after the gas and the maids and gardener there is not enough. The truth is, Mister Jay, I do not know when the phones will be working. Señora Coronado is selling these apartments and she does not want to spend any more money on them. But it is very embarrassing for me sometimes. I do not know what to do.”

“Do you think it would help if I complained to her?”

“Help? I don’t know. But complain if you want, I am tired of complaining, she doesn’t care what I say. Maybe she will listen to you. But she is an angry woman. And a rich woman. I think she does not care what anyone says.”

Instead of the Larga Distancia he went back to the cottage. Elena was arranging tiny figures of a mariachi band on the dining room table. “Look at these,” she called to him. “I found them in a little shop on the plaza. They each have their little instruments, guitars, trumpets, and they all have their little hats.” He looked close to please her, but he went on saying, “I have to go to town and make my calls. It doesn’t sound like the phones will be working soon.”

“OK with me, I like the privacy.”

“Well I do have to keep in touch with the business.”

“Mmhmm,” she replied, repositioning a trumpeter, and he knew she would say no more, seeing in her imagination this conversation with Carolyn.

Then they both heard a voice outside, near the terrace. Jay looked out and walked that way calling back to her, “It’s Favian.” When he led the boy inside Elena was grinning at him, her hands on her hips. “Well Favian!–what do you have?”

His smile was bigger than the first visit. He was washed, his hair combed, he wore nice clothes, perhaps the exceptional smile was for that, how unnatural he felt. He was holding a heavy plastic bag, he opened it to show them.

“Why it’s zucchini!” Elena enthused, delighting him more, and he nodded yes, that’s what they were, calabacitas. A fat bag of them.

“My father gives them to you. He says thank you. For the cans.”

Jay and Elena laughed. She asked the boy, “And what did you buy with the money from the cans?”

He smiled even more, that was his best part. Preening, he touched with both open hands the new shirt, then the pants. The shoes were the old ones showing his toes.

“Why Favian! Those are beautiful clothes. How good! And please thank your father for the beautiful calabacitas.” He nodded yes energetically, he would. Then his eyes wandered to see everything in their cottage again.

Jay said, “Favian, do you have school today?” He made a little shake of the head, but it didn’t really answer the question and it seemed he meant it to be so. Jay leaned toward him and said, “I see. I am walking to the plaza. Do you want to walk with me?” The boy nodded, emphatically yes he did.

The boy and the man walked side by side slowly up Calle Linda Vista, pretty view indeed in the mid-November afternoon that was warm and cool at once, a hot Sun above them, the lush green and shelter of tall matriarchal trees on either side the cobblestoned lane, brilliant orange flutes of llamarada vines cascading over and down the walls they walked beside. Solitary fan palms here and there taller than any tree, etched, gently swaying, upon the seablue Lake Chapala sky.

They turned right onto Ocampo, the plaza a dozen blocks ahead. They passed an empty lot fenced with barbed wire strung loosely, the bottom strand fallen to the ground for half its length, a rusted red sign planted in the center For Sale Chapala Realty, with a phone number . They passed two small houses of gray concrete brick unplastered, frail unadorned roofs warping toward the street, dirt yards each arrayed with six or ten rusted coffee cans displaying stunted flowerless plants. Then they passed a large two-story facade of a lustrous burnt orange presenting an oiled and ornately carved mahogany doubledoor with curving brass handles. Into the broad mahogany of the door’s ponderous frame were carved with care the names of Mexico’s illustrious, Benito Juarez, Emilio Zapata, Francisco Villa, Maximilliano.

“Who lives here?” Jay asked his companion.

“A gringo,” Favian told him. “Rich, very rich.”

A half block further Favian pointed at two old houses up ahead showing their adobe bricks where plaster had washed away, windows without glass, and when they came to them Jay saw that his friend was indicating not the houses but the ample space between those houses that extended far behind and up a slope. Set back was a structure that seemed to have been assembled for the day only, its concrete brick walls unmortared and precariously standing, large pieces of corrugated tin set carefully and overlapping made a roof.

Favian grinned pointing at the house. “It is my house,” he said as another boy a few years older stepped from behind the house into the yard to look at them. Favian hurried up the slope to the flat of the yard and then turned back to Jay and waved for him to follow. Jay followed unsure. The older boy smiled as Jay came to them, Favian beside him grinning as he said “This is my brother Cesar.” Jay offered his hand saying “Mucho gusto, I am called Jay.” They shook hands. “Do you not go to school either?” Jay teased him.

Oh yes he did go to school. In the mornings. School ended at one. Jay saw that this one was bright and attentive, probably a good student. “You gave us the cans,” the older boy said.

“Yes. And I would like to thank your father for the calabacitas.”

“Father works. He is in his garden. By the lake. We have beans and calabacitas.”

“Do you sell them?”

“Oh yes, there is too much for our family. Too much. Do you want to come inside? You can thank my mother.”

“Well I don’t know. I’m a stranger....”

“Oh you are not a stranger, Favian has told us about you. And your wife Elena. And your cats. He showed us the paper with his name on it.” Favian looked back and forth between them thrilled.

The boys led him through the open doorway, Jay saw in the dim light a sofa with cushions mismatched set against the opposite wall, wooden boxes partially draped with bright cloth beside it and others against the adjacent wall. In front of the sofa a table of chrome tubing and speckled formica top. The floor was hardpacked dirt. The wall separating them from another room was unmortared brick like the exterior walls, and upon these were mounted at least two dozen pictures, by friends, from magazines, a black and white Pope and his hands blessing, a red and green postersize Virgin of Guadalupe, a child’s crayoned blue vase of yellow flowers, a pueblo street scene, a sunset on a tropical island prize newspaper photo, and many old framed photographs of faces once young, faces to be remembered, brothers and sisters holding hands in rooms long forgotten or unknown.

A slim small woman came forward from the darkness of a further room wiping her hands on her colorless dress and she smiled at Jay as if she’d expected to find him there. She stopped several paces from him and acknowledged his greeting, both boys going proudly to her side. “I am their mother, I am called Gabriela. Thank you for the cans, you are very kind. Would you have a drink of limonada?”

The roof of tin was less than a foot above Jay’s head. He could smell the cooking, something meaty and strong with chilis. “No, but thank you,” he said, uneasy. “I am going to the plaza, to the Larga Distancia. Favian was going with me.” Favian nodded that yes he was. The mother smiled at this young one. “As he wishes,” she said.

“Then we should go,” Jay told her, glancing to Favian. “You still come with me?” Yes he would. To the mother again Jay spoke, “I want to thank you for the calabacitas. Very, very kind of you. If you may tell your husband for me.” Jay took a slow step toward the door. “Thank you again.” Then another step. In the bright light of the doorway Favian passed outside ahead of him, his brother Cesar remained in the house and said, “Adios,” as boy and man turned and started back across the yard sloping toward the street.

They followed Ocampo through the barrio of Six Corners where Favian waved and called to many of his friends, shyly conscious of the big new friend at his side and the glory of that. At the plaza they turned left passing the police office where a solemn man in brown uniform stood alone in the doorway and stared suspiciously at both man and boy, his carbine in both hands at the ready diagonal across his chest. Passing the video store Jay looked in and saw Judy Tovar, someone he’d been thinking about, alone browsing the selections. He went to her.

Beside her he spoke before she noticed him, “Do you watch movies alone, señorita?” She stepped back startled and looked at him, then her brilliant sparkling smile was there, again to make him wonder like the first time he’d seen her how anyone could not be enchanted by this beautiful woman who still seemed the girl for all her poise and assurance. She was barely five feet tall, her skin was soft Mediterranean, but eyes were dark as the long hair she pulled back from her forehead in the Spanish style and let it hang in a ponytail. And her English was flawless: “Well Jay–I was thinking of you this morning. I was wondering when you would be arriving. Why didn’t you call me?”

“My phone has been out. And I’ve only been here a few days. In fact, I was going to make some calls just now. One to you.” She noticed Favian at his side, grinning at her.

“And who is this? You’ve made a friend so soon?”

“This is Favian. Yes, my little friend.” She greeted the boy in Spanish.

Then to Jay again she said, “I have your plans ready. When can I show them to you?”

“Immediately. But wait–I have another idea. We could meet at the lot, and maestro Lupe could be there, I want you to meet him.”

Her eyes danced, she might have been flirting, or she might have been simply the child of light she seemed to be. “OK–when?”

“Let me talk to Lupe. But we should do it soon...tomorrow if possible. I’ll call you in the morning, I’m sure he’s anxious. I really want to see the plans.”

The store clerk, a very pretty and shy teenager, called to him in Spanish, “Can I help you find something?”

At first he thought no; then he thought again. “What do I have to do to be a member? To check out a video? Do you need a credit card?”

She said, “Oh no, not that. You must know three people.”

He thought he had not heard her right. “I don’t understand.”

“Three people,” she said again. “Three people from the village. Do you know three people?”

He laughed. “Well...yes I do, I think I do. You mean like Judy here?”

She replied seriously, “Yes, like Judy. She is one person.”

Amused at the game he continued, “And what about Favian here? I know him.”

She nodded still serious, “Yes, Favian is another person. I know him too. And do you know another person?”

“Well. Oh yes, I know Anne Dyer, who owns the real estate office on the carretera, Montana Realty.”

“Yes, I know her too, that is enough,” and she allowed herself to relax into a pleasant smile.

He turned to Judy, “How simple . I’m a member now–yes? So you and I can watch videos together–si?” Her eyes sharpened on him calculating, then the radiance returned, the girl spoke, “Ah but you tease me, you are married–yes?”

“Oh not married. But yes, I suppose I am. But I wouldn’t tease you, I like you too much. And you’ll meet Elena when we meet Lupe. No doubt you all will be best friends.”

But it was not until that night Jay found Lupe in the plaza as the church was discharging the hundreds of devoted who flowed like a sea unburdened directly to the plaza one block away to congregate as community in that most inspired center of town, the plaza, to let the children play wherever they would, to watch the parade around the bandstand, to gossip, to eat: the village family.

When they arrived at the plaza Jay and Elena first stopped at the stairs ascending to buy a plastic cup of hot corn from a busy mother and her two daughters who were grilling ears whole in their husks and were boiling in a pan as well ears husked and they afterward separated kernels from cob into the cups and added chili pepper and lime juice to taste. “Not sweet,” Jay said, eating from a plastic spoon, “and hot as hell.” But Elena was only half listening, already looking away to the several hundreds of all ages moving about the plaza or sitting on the dozen and more iron benches around it. Children of all ages chased up and down the bandstand steps. Teenagers strolled in a wide circling of the bandstand carelessly studying each other, girls together whispering, staring and laughing, boys sullen and suave, ready with a quick cool or taunting word to any special girl. Mothers and fathers sat watching all of it, unconcerned for their own children wandering wherever. Grandmothers and grandfathers as well sat and absorbed this too, remembering a lifetime of evenings like this one. Vendors throughout the plaza stood behind cardtables and other makeshift displays selling slices of cake mama had made, or Coke and Fanta, or they grilled chorizo and carne asada to chop into tacos, or sold little two peso toys. Smallest children chased each other and broke hollowed eggshells over another one’s head, laughing as tiny colored confetti spilled into the hair and over the face.

“So I guess this is why they don’t have a theater in town, huh?” Elena said with a laugh as they joined the crowd that was circling the bandstand. The second time around they saw Lupe sitting on a bench talking with a young man beside him and to another standing. Lupe saw them approach and stood to greet them, five and a half feet tall, a little middleage belly, squarish Olmec face, the dark skin of the barrio’s citizens, neat short-sleeve shirt and belted slacks, and always the huaraches.

“So good to see you, señor,” he said in Spanish with obvious pleasure. “I received your note at my house. And is this the señora?” She was already extending her hand to him saying “Mucho gusto, Lupe, I am called Elena.” She was a half foot taller than he, and Lupe looked up to her delighted taking her hand, and then turned toward the younger man on the bench saying, “This is Gerardo, my cousin” and of the older man standing with them he said, “And this is Marcos, another cousin. He speaks English well.”

They shook hands, Marcos as he did so laughing and saying in English, “In the barrio we’re all cousins.” Marcos was tall and handsome, his black hair combed straight back, a slight moustache, his eyes studying them, a man of the world.

Lupe said, “We are starting work soon, señor? All the men are ready.”

“I’m ready too, Lupe. I talked with Judy, the architect, today. She has the plans. We can meet, all of us, at the property tomorrow and look at the plans and talk about what to do. If that is good for you.”

“Tomorrow, perfect.” His was an innocent’s enthusiasm.

“Is you wife here tonight, Lupe?” Elena asked him.

An undecipherable emotion arose in him, altered for that instant the innocence in his face, and then passed away; though the innocence did not return. “Well...I am married, but I do not have a wife. We are not together...oh for eleven years now, she lives in California. With my children.” He looked at them for another moment as if he might say more, but then moved his eyes away and said nothing.

Gerardo, who had listened intently, sat forward on the bench and said warmly, “Lupe is too busy for children now, he has other responsibilities, he keeps the rest of us out of trouble. Eh, Welequi?” Marcos laughed.

“I don’t know that word,” said Jay.

“It means mother hen,” said Marcos. “Lupe keeps watch on all the bad cases in the barrio. Like Gerardo here.”

“The drinkers,” said Gerardo laughing also and glancing to Lupe. “The trouble-makers.”

“You don’t drink, Lupe?” asked Jay.

Gerardo said, “He is jefe of the alcoholics anonymous.”

Lupe, somber, shook his head. “Eleven years. Nothing.”

“I do not drink either,” said Gerardo sitting forward.

Marcos laughed, spoke to Lupe in Spanish as if it would be a private joke, “After your adventures, uncle, there was nothing left for anyone to drink.”

Lupe stared two seconds at him coldly, then turned again to Elena with his original smile and said, “You will be there tomorrow also, señora?”

“Of course, Lupe. And every day.”

A woman approached and stopped beside their bench, she wore a dark simple dress, a black shawl over her shoulders gathered in her hands at her waist. Lupe looked at her and rose immediately, saying to them, “I present my sister Carmela. Jay, his wife Elena.” She smiled and took their hands, speaking to both, “A sus ordenes.” She was perhaps a few years older than her brother, their eyes and squarish faces alike. Gerardo then too rose. Lupe said, “I must excuse myself. We go back to our house.” But before moving further he looked to Jay and said, “At what hour tomorrow, señor? As you like.”

“At one then. You remember the lot?”

“Oh yes. I remember well. Goodbye, señora.” And those three turned away and disappeared into the crowd.

Marcos said, “Sit. If you have time. I enjoy all this, Lupe would rather stay home.” All three sat and for a long moment watched the multitude passing before them.

Finally Jay asked, “Do you do construction too, Marcos?”

He shifted position. “Yes I do. I ‘m a plumber and electrician. I work with Señorita Tovar sometimes. And with others.”

“Well. Perhaps you could do that work for us. I don’t know if it’s customary for Lupe to say who does that work or not. Or maybe Judy decides that. We’ve never done this before.”

“No, it is for you to chose. And if you want me to do that work I would do it.”

“Where did you learn to speak English so well?”

“I lived in California four years. I worked construction. Carpentry. And plumbing.”

“Why did you come back?”

“All my family’s here. All my friends. Life’s easy here. It was...how to say...very exciting in California. And we had some wild times there, and I liked that. But it was time to come home. Many of us destroy ourselves there. Many ways it is possible.”

Jay shuddered. Elena, leaning forward and slightly toward their new friend, said, “I was sorry to hear about Lupe being separated from his family. I could see how much it bothered him.”

Marcos laughed. “Yes, about the children it bothers him. But not about the wife, she still curses him.” Elena winced. “Many years ago he was a wild one.” He laughed remembering, then his voice turned uptempo. “I know he wouldn’t care if I told you this...but Lupe and my father were the worst borrachos in town, man. This was fifteen, twenty years ago. They would go down to the lake every morning after buying a big big bottle of this terrible pulque, it was white and nasty and it probably only cost three or four pesos for two litros. Made by some old man in town. And they would drink all day, mixing it with water from the lake until they passed out in the afternoon and we had to help them back to their houses for comida. They were eight crazy friends who drank every day together like that. They did it for years. For years. All of them were young. But now all the rest of them are dead. A long time dead. Only Lupe and my father are still living. Lupe has a lot to live down, man, even all these years later. His wife didn’t have to make up any of her complaints.”

Lupe was waiting for them at the lot, standing toward the middle of it hands on hips and studying a tall pine that grew in the center of the lot. Elena parked the van curbside behind what they assumed was Lupe’s twenty-year-old white Toyota and Jay stepped carefully through tall stalks of weeds and grass gone to seed and heavy stones toward him. Elena found a path worn diagonally across the property by local pedestrians and she walked that way and looked side to side with great pleasure imagining bedrooms there and terraces and hidden alcoves.

Their lot adjoined another vacant like it at the corner. At the rear a brick wall eight feet high blocked their view of a parking lot and its double row of cheap apartments. To the east another brick wall the same height separated them from their neighbor’s house. A hundred homes or more had been built on these conjoining and serpentine streets more or less thirty years before and the neighborhood was called Chula Vista. Only the homes built upslope of the general flat had views of the lake. All the streets and yards were lush with tall trees and the reds and purples of hibiscus and bougainvilla and other colors more subdued of dozens of other tropical flowers and trees blooming year round.

“A fine property, señor,” Lupe said to him glancing at the naked earth around them. He wore old denims and a clean blue shortsleeved shirt buttoned taut over his stomach. And huaraches. “Have you made a day to begin?”

Jay laughed. “Lupe, I know nothing of what we are doing. I am here to learn. What is necessary to begin? You tell me.”

Lupe looked at him and saw this was the truth. He looked back at the earth and seemed to study it, then turned his eye back to Jay and said with confidence, “It is nothing complicated. We order rock and river sand and cement and cal and the rebar called Armex, and we begin. We can begin tomorrow. If it pleases you. I will bring the men at eight in the morning. The architect is coming with the plans today–yes?” Jay nodded yes.

Elena came beside them, spoke greetings to Lupe, and he in return to her. Then all three turned to watch a new Ford Bronco metallic bluegray turn the corner and park behind the van. Judy stepped from the Bronco, Texas licenseplate BUSTER, wearing a sleeved blouse of pastel flowers and new levis and white jogging shoes, very pretty, her pony tail swinging sideways, anyone might have thought her less than thirty years. She held a paper cylinder in one hand and a notebook in the other, and she smiled brightly to all of them as she came across the sidewalk.

Lupe said to Jay softly, “This is the architect, señor?”

Surprised, Jay answered, “You have not met the señorita, Lupe? I thought you knew everyone.” For whatever reason he did not answer, and as Jay introduced him to her he was again gracious and said he was pleased to know her, that he had seen her houses in the village, several of them, so well done.

Then she looked at Elena and smiled. “You must be the señora of Jay.”

Elena shook her head amused, “Oh that’s much too formal, we’re not married, I’m still trying him out.”

Judy laughed. Jay smiled. Then she unrolled the plans at arm’s length for them all to see, but she saw for the awkwardness that wouldn’t do, and said for them to come to her Bronco, and there she unrolled the plans again holding the big sheet flat on the hood of her vehicle so the other three could come close and see what she had made. She pointed out two bedrooms on a ground floor, two bathrooms, a living room-dining room, two fireplaces, the kitchen, the back terrace; and a loft bedroom on a second floor with its own little terrace and another bathroom. “Oh I love the loft,” said Elena. Judy said in English, “Yes, from your upper floor terracita you will have a view of the lake,” then repeated it in Spanish for Lupe.

He made a wry smile and said, “But two floors are not permitted in Chula Vista, architect.”

Unruffled she said, “Not exactly true, maestro. The restriction is a five meter height limit from the street level. We will be able to make two stories because we will excavate down a meter or so and that will allow us the height we need to make two floors.” The maestro nodded oh yes I see, but he seemed instead to doubt it.

Jay said to her, “Lupe thinks we can begin as soon as tomorrow. What do you think?”

“Tomorrow?” She looked at them all puzzled. “But maestro, we have not even submitted the plans for permission. And what if señor Jay and his señora want me to make changes? We cannot be in such a hurry.”

The maestro looked away irritated. She went on. “And there are other things to be established. I have a responsibility to my clients. Since you are to be their maestro I need to ask you certain questions. Even though they have chosen you. You have built a house of two floors?”

He looked at her. Perhaps he could not say what he wanted, for a strain showed in his taut lips. He did say, “Yes, I have built two floors. I have done construction all my life, architect.”

She continued pleasantly, this difficult woman that seemed to be only a girl playing at this. “Alright. And what proportions do you mix for foundations?”

He forced himself to say “Two carts of riversand and one cement and one half of cal.”

“And you reinforce the Armex that you use in the dalas and the castillos?”

“Yes, architect. With three-eighths inch.”

“Good. And you have worked with plans before I assume. I ask not because I doubt your experience, but because, as we both know, many houses are built in the village from simple drawings in pencil. Or from lines drawn in the dirt with sticks.”

He was impatient for her to finish, “Yes yes,” he said, “I can read the plans, I have done many houses this way.”

She let the plans roll themselves back into a cylinder on the hood of her Bronco and then handed them to Jay. “Take these home and look at them. Take your time. You will probably want to make changes. It is easily done.” Then she looked back at the lot. “And this is a beautiful site for a house. You chose well. There are other areas of the village I like better but houses in Chula Vista sell very well, very quickly, at a good price. And that is your intention–true? To sell the house?”

“Yes it is,” Jay said to her. “And there’s something else I want to speak to you about. I haven’t brought this up till now, but I have a special request. I know that usually you supervise the construction and take care of everything. I mean just keeping it rolling, ordering and paying for the supplies, doing the payroll, all of it. Watching the men. But I want to do that myself. Obviously I have no experience. But I want to come here every day and do whatever it’s possible for me to do. I think I could do all those things. If you could help me. So I mean...instead of paying you the figure that you quoted me to build us a house, I’d like to pay you a set fee to help me do this myself. Pay you to be a consultant. I mean, I would be here every day, you would only have to come...sometimes...or when I called you with a problem, something I didn’t understand. Do you see what I mean? I want to do this myself. To learn how it’s done.”

She considered only a moment. Then showed him the smile she used to enthrall everyone and said, “Of course. Yes, we could do that. And what would I charge you?” She considered again. “Let’s say a thousand dollars a month for five months. Is that reasonable?”

He sighed his relief, extremely happy, and said, “It’s more than reasonable, it’s very generous. Thank you, this was very important to me.”

“I understand.” She gave him her delicate hand. “Then we have a deal. And now I must leave, I have another appointment, in Guadalajara. Very good to meet you, Elena. And you also, maestro. And as soon as I have the plans back from the señor and the señora, we can have them approved in a few days, don’t worry yourself. Adios. Until I see you again, maestro.” And she hopped over a stone as she went to the sidewalk, her black ponytail swinging, and went to her Bronco and drove away.

They all three watched her go. Lupe turned to Jay and said in a soft voice, “No doubt she is a good architect. But in the old days it would not have been done. Yes, women may draw plans, I understand that. But the construction site is no place for a woman. Twenty-five years ago, when I began, it would not have been permitted. Never.”

3: Back to SF

Three days later Jay answered the knock at their cottage door and saw Lupita with an extravagant smile already speaking her excitement as he opened the door. “Oh Señor Jay, I think the phones must be working, would you listen on yours?” Jay went to the set on the kitchen counter wall, listened and rehung it. “No,” he said returning, seeing her frown. But she was not so easily deflated, going on again exuberantly, “Oh well I thought the phones in the room might work. Because...the phone in the office rang just now, and it shocked me so that I dropped my glass of milk--it was the operator from the United States and she said in English that she was making a call for you.”

“Did she say who was calling?”

“No señor. But whoever it is is still waiting for you. I ran all the way down here to tell you.”

She led him up the long path beside the flourishing flowers and ferns and swordplant, both of them greeting as they passed him the young gardener kneeling to trim away the dead leaves from calla lillies, Lupita calling him Rogelio.

Inside the office she handed him proudly the phone.

“Yes?” he said. It was Carolyn, he asked, “How’s everything?” He half held his breath.

“Not so good. I’ve been trying to reach you since yesterday. Listen–Dennis got busted yesterday, they raided his house, not the store. He’s in jail, or he may be out by now, I can’t find out. But...the cops got a lot of pot and a lot of money. And they got the five units you fronted him just before you left, the ones I’m collecting for. I already told Mr. B about it, and he’s OK...for right now...but I know you can’t afford to cover this. I figured it’s about seven thousand dollars. I hate to call you with this bad news but I just didn’t know what to do.”

He waited for his own inspiration to come and dampen the rising tide of nausea he was feeling. “Well.” But nothing came. “Alright. It’s good you’ve already talked with Mr. B. Of course he’ll give us all the slack we need. But the important thing will be to get to Dennis, I need to talk to him. Keep calling at the house and at the store. You do have both numbers, don’t you?” Yes. “OK. Now don’t worry. Any more than you can help it. And stay away from Dennis’ house and the store, you got that? Only call him from pay phones. Keep calling till you reach him. If you can’t get him, talk to Steve. What I need you to do is to set up a time when I can call him from here. This is crucial.”

“Jay, this has me a little nervous.”

“I know, but don’t worry, you’re completely out of reach. No one knows the home phone number and no one knows where you live. Dennis has never even known my last name.”

“Jesus–is that true? After selling to him twenty years he doesn’t know your last name?”

“That’s right. You’re out of reach.”

When he returned and told Elena she shuddered. “This doesn’t mean you’ll have to go back, does it? Surely Carolyn can deal with it.”

“It all depends on what Dennis has to say.”

Phone service was lost again at the Villas Ajijic and Jay walked several times a day to the Larga Distancia by the plaza to call Carolyn but it was not until the next evening that she had news for him. “OK, I finally talked to Dennis. He’s out, and he wants to talk to you. He said he’d be at the house tomorrow all morning.”

“How did he sound?”

“Oh he was very up, sassy as hell, the cops must just dread dealing with this guy.”

With the two hour time difference Jay paced the plaza till 11:30 before calling from the tiny booth at the rear of the Larga Distancia. “Jay-O, great to hear you, how’s Mexico? It’s raining like hell here.”

“Mexico’s good, Dennis, sunny. But what about you? Can you talk?”

“Oh hell yes, I got no secrets, I hope the DA is listening. You probably heard about the bust. Sorry about those pounds of yours, but I’ll make it up to you, you know that. They got more than a hundred units and about eighteen thousand dollars. But we’ll be OK, everyone’s willing to give me a little time. You haven’t seen my store recently, have you?”

“Not the new one. You moved just as I was getting ready to leave.”

“OK. Hey--I’m revolutionizing the pot business. But we can talk about that in a minute. First I want to get your money back to you, but I’ll need a little help. A couple of the old faithful are still working with me, you know, fronting me a little here and there till we can get rolling again full tilt. Most of the people whose pot got confiscated were big and they can afford to wait a while for their money. But I know that for you and Carolyn this is a hard one, and I want to make it up to you as soon as possible. This is what I need from you. Can you get any more of that really fine Mex you were giving me?”

These details to Jay seemed to derive from a world remote and obscured by fog or dark smoke. He thought. “I suppose so. I’ll have to ask my guy.”

“OK ask him. Then if you can do it, I want you to bring me one or two at a time, whatever you feel safe with, and I’ll pay you up front for whatever you bring. Got that?–I’ll pay you for what you bring me. And then when I sell them, in a day or two, you can come back with one or two more and I’ll pay you for those two and pay you for two of the ones that got picked off by the cops. See what I mean? I’ll pay you in advance each time, and in addition pay you for one or two I owe you for. Within a week or two you’ll be paid off and you’ll have sold five new ones. And maybe somemore.”

“Could work. But Carolyn can’t make these kind of transactions.”

“No Carolyn shouldn’t do it, it has to be you.”

“But this is making me sick thinking about doing this again. I can’t tell you how great it feels to be far away and to go for days at a time without thinking of the business.”

“I know, Jay-O. But you could be in and out in a week or so. Get your money back. And make a few extra thousand on top of it. And there’s something else. I want you to see the store. I’m making history, man, I want you to see it. I want you to write about it.”

“Write about it? What are you talking about?”

“You still write, don’t you? Remember that great article you wrote about me twenty years ago, it was called “Dennis and the Armies of the Night.” It was a chapter in a book you’d written about the dope business. I still have that chapter. I read it again just the other day, man that was good. It was the best thing that’s ever been written about me. And you know I’ve got scrapbooks filled with newspaper articles and stories about me and about the Marijuana Initiative. And I need publicity, man, especially now. I need good publicity.” Jay’s adrenalin buzzed as the memories rose up in him and took flight.

“What’s happening at the store?” he asked.

“The revolution,” Dennis said, his own adrenalin pulsing, “I’ve found the crack in the armor and this time I’m gonna break through. It’s marijuana as medicine. I’ve got fifteen doctors backing me, they’re giving out prescriptions for fucking pot! To AIDS patients, to people with glaucoma, to anyone who’s suffering and needs pot to help them live. I’ve got four hundred prescriptions on file and we’re dispensing pot like a pharmacy. It was the State police that popped me, the local cops come by every day, they always ask us how we’re doin’ and they let us alone. Man--you gotta come and see it!”

“I don’t see any other way to get the money back,” he said to Elena, whose head hung and swayed with an infinite sadness hardly perceptible. “I know it feels like going backwards. But I have to get that seven thousand. It’s just not something Carolyn can handle. And, not unimportant dear, I’ll make a few thousand on top of that. Which we could certainly use. And I’ll only be gone a week. At the most.”

He flew United at 7 AM out of Guadalajara through two time zones and arrived SF International ten minutes before 9, was through customs in five minutes with his single carryon, rented a white Dodge Neon and drove through the City up 19th Avenue and across the bridge. The wide sparkling bay brought the great beauty of it all home to him again, the sailboats, the tall white buildings on their cluster of hills to the shoreline, seagulls gliding among the bridge spires, magnificent. And still green were the hills of Marin as he passed through them on 101 north, the freeway signs he’d known daily for thirty years now seemed like startling remnants from another time, Tamalpais, East Blithedale, Corte Madera, Francisco Boulevard, then San Rafael where he exited and from there he might have done it asleep for all the hundreds of times he’d let his car lead him through the business corridor west through San Anselmo and over White’s Hill down into Fairfax and through that hillbilly backwood and up the curves that recurved twenty times until he slowed and stopped behind Mr. B’s four year old dark blue Mercedes sedan hidden away among pine trees.

In a big house with no visible neighbors Mr. B answered the door in house slippers, cut off levis and a gray longsleeve sweat shirt, a cup of coffee in his hand. “Well, you got here fast,” he said with a handsome smile. “Let’s go to the office. How about a coffee?”

Jay, holding an empty worn backpack, said yes he would and Mr. B called into the kitchen, “Carla, bring us a coffee please,” as Jay followed him through the long living room he knew so well, shiny oak floors with several expensive oriental carpets askew, a stone fireplace never used, castaway sheets of the morning Chronicle on the leather sofa and on the beige carpets, carpets which extended down the hall where Jay glanced as he always did at the collection of old Fillmore and Avalon posters all framed, half of them signed by Mouse and Kelly and Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso and others whose fame lived only in the memory of these old hippies.

The office was large with a big window behind the desk framing the pine-covered downslope of his hill and a creek barely visible at the base of it and the far slope rising away to the west, oaks and elms going red and gold there among the pines, each leaf and toss of a tree limb in the breeze perfectly highlighted in the late morning Sun.

Jay sat as he always did in the soft chair in front of the desk, Mr. B going to his swivel chair behind. A large white sofa was against the opposite wall, a glass and wrought iron coffee table before it, several large softcolored innocuous gold framed paintings were on the walls. Right of Jay was a small desk beside the principal one supporting a computer tower and monitor which displayed a stock market ticker flowing across the screen in silence.

“How’s business?” Jay asked, nodding at the screen.

“That business is just so-so. I’m trying out two new companies, but they’ve disappointed me the last couple weeks. But the other business couldn’t be better. I’m sorry to hear what happened with Dennis.”

Mr. B in his chair leaned toward him, eyes bright and cheerful, Italian face well tanned, both dark hair and beard cut close, the gray in both handsome defining the sharp lines of face and head. He wore neither rings nor bracelet nor watch.

Carla quietly entered and handed the coffee to Jay, who smiled at her, “Hi Carla.” Pleased to see him she said, “Hello, Jay, I thought you were in Mexico.” “I am, this is just a quick vacation. He isn’t working you weekends, is he?” “Oh no, never that. See you again.” She turned and left them.

Jay turned to him, “Oh I never worry about Dennis, the guy is indestructible. He’s got some medical marijuana scam he’s ranting about, I’m going over to see his new operation after I leave you.”

“Oh yes, I heard something about that. He’s getting signatures to put it on the state ballot for the next election. In the voting last week in San Francisco he pushed through an initiative about medical marijuana, calling it Prop 215, and it passed by...oh my god, I think it was something like seventy percent. I hear the mayor and the local police are sympathetic.”

“That’s what he’s telling me.”

“So he wants us to bring him some more pot, eh?”

“Yea. Like I told you, he’ll pay for what I bring him, and then the second round and from then on, he’ll pay me for the ones that got popped.”

“Fine with me. But what about you? Aren’t you worried about delivering them when the cops might be watching him?”

“A little. But I’ve worked with him in situations like this before. No, I’m not really worried.”

Mr. B grinned. “OK. I’m not if you’re not. How’s Elena?”

“Fabulous. I think she really likes it down there, so far. But she is really bummed out that I’m having to come back here and do this.”

“I can imagine. Well let’s get you going. You say you want two?”

“Yea. They’re like the ones I fronted him last time, aren’t they?”

“Yes. This is the last bale of it. A nice product.”

Mr. B rose and walked to a closet, slid a mirrored door of it open and lifted out a dark green plastic bag secured with a twist-tie, and handed it to Jay. Jay opened it, saw two other plastic bags inside, looked briefly into each one, then resecured both smaller ones and again the outer bag and put it all in the backpack he’d brought with him.

As he exited the front door he said, “I’ll stop back this afternoon with the money for these two. I’ll call first.”

“Always good to see you. Good luck. Be careful.”

Jay set the backpack in the trunk and drove again the exact route he had come, stopping only at a Burger King in San Rafael to buy a Whopper with cheese and fries and Coke, which he consumed one handed driving 101 south toward the bridge and the fabled city which had been his life and joy and excitement for thirty years.

He sped his little Neon through the Sunset and Golden Gate Park and along the Panhandle bordering the Haight, every block of it driven a thousand times, a deathly trail of old pathetic memories that leaped at him from street signs and lamented apartment buildings, an old latenight beer store, favorite phone booths, an intersection where they’d stopped him seventeen years ago and searched the car, by some miracle had not seen his contraband, and let him pass on. He went without thinking his old shortcut by Buena Vista Park that dropped him onto Divisadero and then down toward the Castro, going left onto 16th Street crossing Market and he found a parking place half a block from Dennis’s house near Sanchez. Mexico seemed as if it never had been.

He knocked, empty handed. A thin handsome teenage boy opened the door, ready to please him, yes Dennis was there, and turned barefoot down the hall leading him to the front room he’d entered surely far more than a hundred times in the fifteen years Dennis had owned the house. Two other young ones, one without shirt, sat gossiping face to face on the sofa, hardly glancing to see who he was, as his escort stopped and pointed at the doorway to Dennis’s bedroom and office. Jay entered.

Dennis was sitting on the bed dressed in levis and blue denim shirt, thin, a happy if lined and expressive face in which the incessant wars he’d waged upon the police and the political bureaucracies had only made more vibrant. His hair hung in unkempt strands to his shoulders, gray now some of it. He’d been talking to a handsome young boy beneath the bedcovers watching as Dennis turned to Jay and said exuberantly, “Jay-O! That was quick.” Standing, going to him, they embraced.